This indicator provides a measure of the extent to which forest dependent Indigenous communities are able to respond and adapt to change successfully. Resilient forest dependent Indigenous communities will adapt to changing social and economic conditions, ensuring they prosper into the future.

This is the Key information for Indicator 6.5d, published July 2024.

Information on the resilience of forest-dependent communities to changing social and economic conditions is presented in Indicator 6.5c.

- Australia’s Indigenous peoples have a deep connection to ancestral landscape and forms part of a sense of wellbeing. Access to forests enables Indigenous people to maintain or re-connect with cultural values, strengthening personal and community resilience.

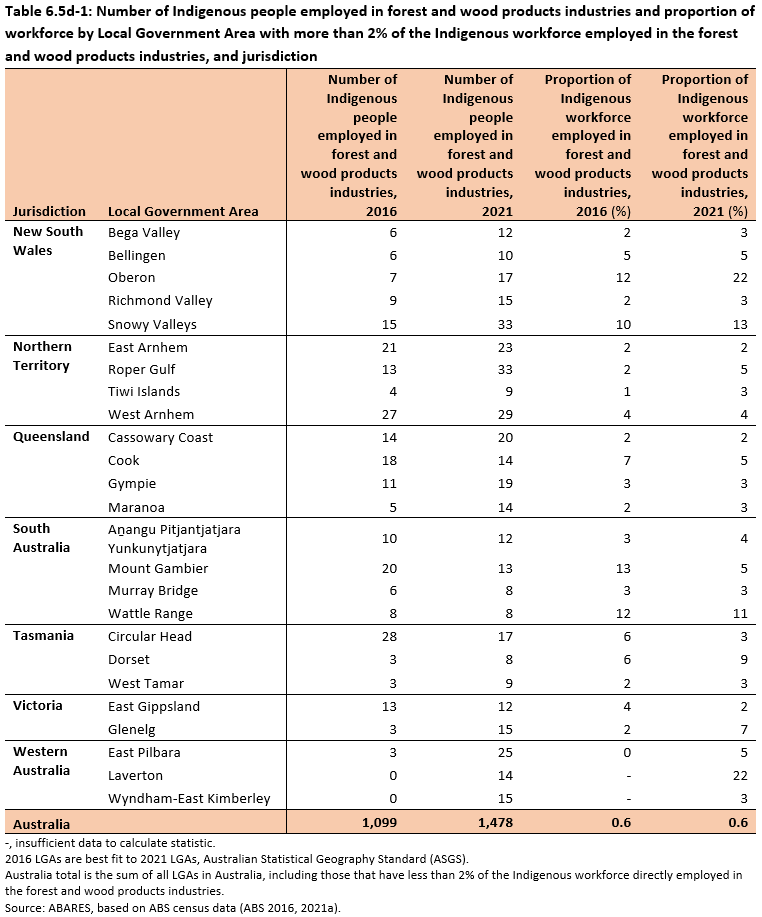

- The forest and wood products industries directly employed a total of 1,478 Indigenous people nationally in 2021, an increase from 1,099 employed in 2016.

- A total of 25 Local Government Areas (LGAs) had more than 2% of the Indigenous workforce directly employed in the forest and wood products industries in 2021.

The deep connection of Indigenous peoples to their ancestral landscapes is central to well-being (Kingsley et al. 2013). Many Indigenous people place strong cultural significance on native forests, and activities that occur on forested land. Access to native forests enables Indigenous people to maintain or reconnect with cultural values, strengthening their connection with land and the past (Feary 2007; Feary et al. 2010; 2012; Hunt 2018). This strengthens individual and community resilience.

The cultural use of native forests allows Indigenous people to connect with ancestral landscapes through activities such as hunting, collecting bush food, use of fire, collecting materials for arts and tool-making, and sharing stories and social ceremonies. Native forests are places where new generations of Indigenous people can learn traditional knowledge about Country and its values, thereby contributing to the cultural resilience of their communities. This strengthens Indigenous mental health and personal wellbeing (Feary 2008). Cultural dependence on forests is particularly strong when the forest involves Country for which a particular Indigenous community has customary responsibility (Ganesharajah 2009; Kingsley et al. 2013).

Cultural burning is an example of a cultural, forest-based practice that engenders individual and community feelings of well-being and satisfaction. Embedded in millennia of traditional activities, it forms a core part of Indigenous cultural identity and pride, including staying connected with the land and with each other. Using fire involves intricate traditional knowledge passed down from generation to generation, and is nested in ancient spirituality, customary laws, traditions and social organisation. Cultural burning facilitates community gatherings and collective activities, allowing for story-telling, advocating values and enacting traditional roles in communities. Indigenous fire management practices have a crucial purpose of maximising plant and animal food resources and managing the environment from which they are drawn (Gott 2005; Fletcher et al. 2021).

Generally, the most resilient Indigenous communities are those in which economic development incorporates customary laws and values. Natural resource management activities and culture-based employment, such as with Indigenous land management programs, provide economic, health and wellbeing benefits to communities (Kingsley et al. 2013; Garnett et al. 2016). These are particularly important in remote communities with limited access to commercial industries.

A range of forest-based activities provide economic benefit as well as facilitating cultural connections to forested areas, including:

- Cultural heritage assessments associated with forest management activities may be legislative requirements, and provide opportunities for Indigenous people to earn income and to reconnect with and conserve culturally significant places.

- The Indigenous Ranger program, part of the Australian Government’s Working on Country program, incorporates customary law and values into land management (Garnett et al. 2016).

- Savannah fire management for carbon credits relies on the application of cultural fire knowledge to undertake early dry-season burning and limit late dry-season burns, with income generated from associated carbon emissions reductions used to improve the well-being of Indigenous people connected to that land (Altman et al. 2020).

- Wattle seed harvesting for commercial purposes (predominantly gundabluie, Acacia victoriae) by Indigenous women across South Australia and the Northern Territory is based on traditional practices (RIRDC 2014).

Together with financial security, other benefits of cultural forest-based employment include strengthened individual self-confidence and self-esteem, better lifestyle choices, improved health and wellbeing associated with outdoor activity, and involvement in meaningful work. The benefits of being employed often extend to the individual’s immediate and extended families. For Indigenous people, broader community benefits include stronger community leadership, positive role models for younger generations, and stronger bonding between elders and younger generations that facilitates the passing on of traditional knowledge (Van Bueren et al. 2015; Stoeckl et al. 2019).

Economic dependence on forest-based activities is difficult to quantify because of the diverse ways in which Indigenous people may be engaged in forest-related employment. The number of people directly employed in forest and wood products industries is used here as an indicator of the economic dependence of Indigenous communities on forests.

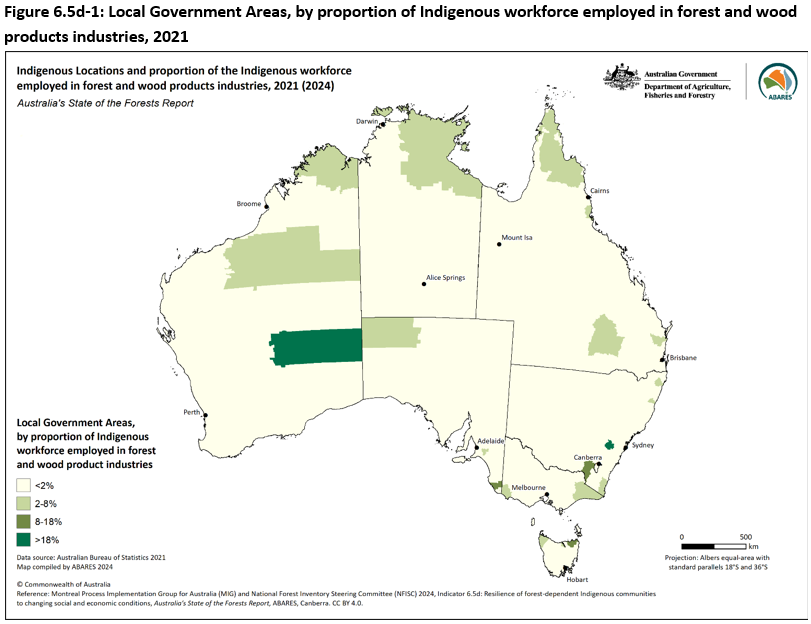

In 2021, there were 25 Local Government Areas (LGAs) with more than 2% of the Indigenous workforce directly employed in the forest and wood products industries (Table 6.5d-1, Figure 6.5d-1), with a total of 1,478 Indigenous people nationally (0.6% of the total Indigenous workforce). Some of the LGAs with higher numbers of Indigenous employees in forest and wood products industries included Snowy Valleys in New South Wales, Roper Gulf, West Arnhem and East Arnhem in the Northern Territory, and East Pilbara in Western Australia.

The proportion of Indigenous persons working in forest and wood products industries increased in 14 of these LGAs between 2016 and 2021 (Table 6.5d-1). This may reflect increased opportunities to provide advice and services to commercial forestry operations, or acting on an opportunity where forest resources become available. Decreases may be due to changes in the forest and wood products sector as a whole, or the availability of employment in other industries.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 6.5d-1.

Click here to download a high-definition copy of Figure 6.5d-1.

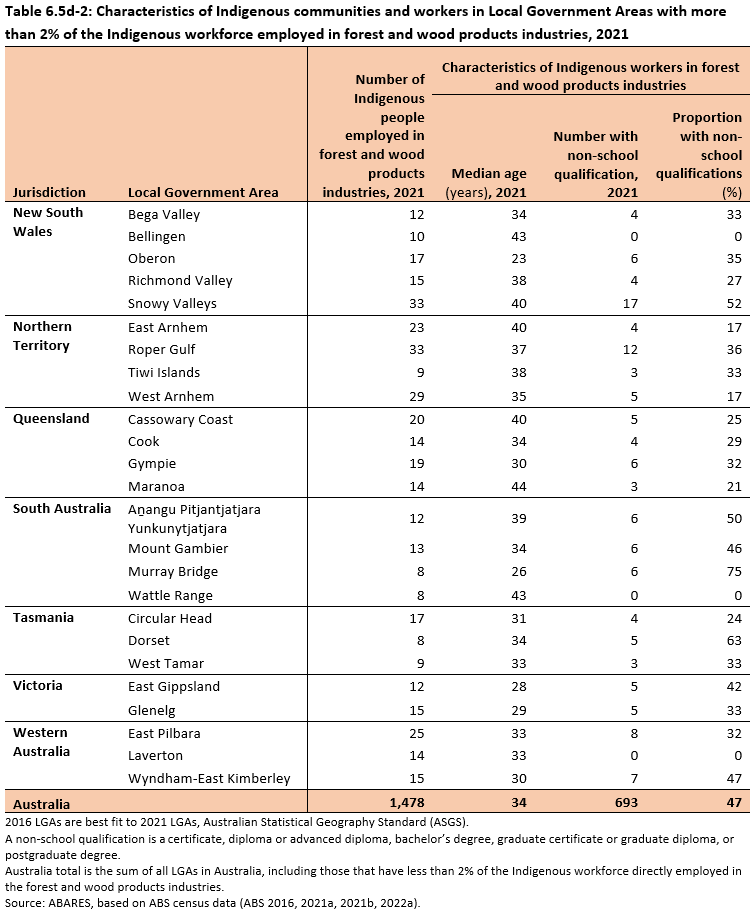

Factors such as an individual’s skills, age, education and financial resources are key influences that support adaptability and positive wellbeing outcomes. There is also a strong link between increased education levels, and improved employment and health outcomes for Indigenous people (Commonwealth of Australia 2018). Employment is associated with improved wellbeing and living standards, and benefits individuals, associated families and broader communities. Demographic information about Indigenous people employed in the forest and wood products industries can therefore be used to understand their resilience to change in forest and wood products industries.

Indigenous worker median age, qualifications and financial resources vary across the Local Government Areas (LGAs) with more than 2% of the Indigenous workforce employed in forest and wood products industries (Table 6.5d-2).

- The median age of the Indigenous forestry workforce was 34 years, ranging from 23 to 44 across the 25 LGAs.

- In general, younger employees can find it less challenging than older employees to find alternative employment.

- Workers had higher levels of non-school qualifications (such as certificates and diplomas) in Aṉangu Pitjantjatjara Yunkunytjatjara and Murray Bridge (South Australia), Snowy Valleys (New South Wales), and Dorset (Tasmania) than in other LGAs.

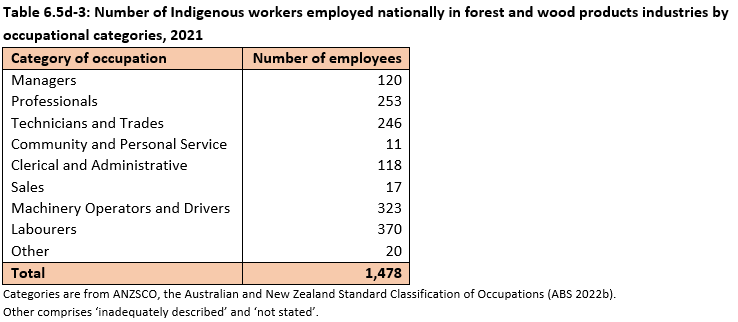

Nationally, many Indigenous persons work in higher skilled occupations (Table 6.5d-3). For example, in Roper Gulf (Northern Territory) the majority work as ‘professionals’, while in Snowy Valleys (New South Wales) the majority work as ‘machinery operators and drivers’. Low skilled and high skilled work is commensurate with qualifications and experience.

The skills and work experience gained in forest-based enterprises or occupations can assist Indigenous people to obtain employment in other sectors. For example, Indigenous ranger programs have contributed to preparing Indigenous people for subsequent careers (Van Bueren et al. 2015; Stoeckl et al. 2019).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 6.5d-2.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 6.5d-3.

Altman J, Ansell J, Yibarbuk D (2020). No ordinary company: Arnhem Land Fire Abatement (Northern Territory) Limited. Postcolonial Studies, 23(4). doi.org/10.1080/13688790.2020.1832428

Commonwealth of Australia (2018). Closing the gap: Prime Minister's report 2018, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra: 132 pp.

Feary SA (2007). Chainsaw Dreaming: Indigenous Australians and the forest sector. Australian National University, Canberra.

Feary S (2008). Social Justice in the Forest: Aboriginal engagement with Australia's forest industries. Transforming Cultures eJournal 3(1). doi.org/10.5130/tfc.v3i1.683

Feary S, Kanowski P, Altman J, Baker R (2010). Managing forest country: Aboriginal Australians and the forest sector. Australian Forestry 73: 126-134. doi.org/10.1080/00049158.2010.10676318

Feary SA, Eastburn D, Sam N, Kennedy J (2012). Western Pacific. In Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge, Parrotta, JA & Trosper, RL, eds. (pp. 395-447). Springer, Dordrecht. doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2144-9

Fletcher M-S, Romano A, Connor S, Mariani M, Maezumi SY (2021). Catastrophic Bushfires, Indigenous Fire Knowledge and Reframing Science in Southeast Australia. Fire 4(3): 61. doi.org/10.3390/fire4030061

Ganesharajah C (2009). Indigenous health and wellbeing: the importance of country. Native Title Research Unit, Australian Institute for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.

Garnett ST, Austin BJ, Shepherd P, Zander KK (2016). Culture-Based Enterprise Opportunities for Indigenous People in the Northern Territory, Australia. In: Indigenous people and economic development - An international perspective (eds: Iankova K, Hassan A, L'Abbe R), pp. 131-152. Routledge Taylor and Francis Group New York.

Gott B (2005). Aboriginal Fire Management in South-Eastern Australia: Aims and Frequency. Journal of Biogeography 32(7): 1203-08. jstor.org/stable/3566388

Kingsley J, Townsend M, Henderson-Wilson C, Bolam B (2013). Developing an Exploratory Framework Linking Australian Aboriginal Peoples’ Connection to Country and Concepts of Wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 10: 678-698. doi.org/10.3390/ijerph10020678

RIRDC (2014). Focus on wattle seed (Acacia Victoriae). Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation and Australian Native Food Industry Limited.

Stoeckl N, Jarvis D, Larson S, Grainger D, Addison J, Esparon M, with contributions from Bidan Aboriginal Corporation, Bunuba Dawangarri Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Ewamian Aboriginal Corporation, Gooniyandi Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC, Hill R, Pert P, Poelina A, Ross J, Walalakoo Aboriginal Corporation, Watkin-Lui F and Yanunijarra Ngurrara Aboriginal Corporation RNTBC (2019). Multiple co-benefits of Indigenous land and sea management programs across northern Australia. James Cook University, Townsville.

Van Bueren M, Worland T, Svanberg S, Lassen J (2015). Working for our country: A review of the economic and social benefits of Indigenous land and sea management. Melbourne, Pew Charitable Trusts and Synergies Economic Consulting.

Further information

- Data sources

- Defining resilience

- Cultural burning as a forest-based activity

- Case study 6.5-d-1: Traditional Indigenous burning and koalas on the south coast of New South Wales