This indicator is used to assess the sustainability of the harvest of non-wood forest products. These products can represent a significant asset base supporting the livelihoods of remote communities.

This is the Key information for Indicator 2.1d, published December 2025.

- A wide range of non-wood forest products are produced in Australia, including honey, wildflowers, crocodile skins, kangaroo hides and meat, and aromatic products derived from sandalwood.

- State and territory governments regulate the removal of non-wood forest products, including through setting annual harvest quotas, and the issue of permits and licences.

- Non-wood forest products are vital for Indigenous Australian people and communities as they support cultural practices, livelihoods, and connection to Country.

Australia produces a wide range of non-wood forest products. Non-wood forest products, and associated management plans are reported in this indicator, while details of economic value are covered in Indicator 6.1b. Forest ecosystem services relating to soil and water, and carbon values are discussed in Criterion 4 and Criterion 5, respectively.

The Australian, state and territory governments have regulations to limit and control the removal of plant and animal products from forests, including commercial harvesting. Some key regulatory instruments are summarised in Box 2.1d-1 below. Relevant government agencies in each jurisdiction regulate permits or licences for harvesting, including hunting. Permits are usually only issued after a detailed sustainability analysis, which is based on population monitoring. These analyses consider factors such as current local population levels, population trends, reproduction rates, and threats or pressures such as disease or habitat loss.

The Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) sets the overarching framework for managing native wildlife, particularly for species that are traded internationally, such as kangaroos and crocodiles. Harvesting of native species, including allowable rates of extraction (quotas), vary by state and territory. Annual harvest quotas are specified for each species by the relevant state agencies. The quota and management plans are then endorsed by the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water. The annual harvest quotas vary from year to year, based on consideration of population trends, previous harvests and seasonal conditions. Across Australia’s states and territories, harvesting or removal of native animals and plants from nature conservation reserves is not permitted.

Harvesting of introduced feral species does not require sustainability analyses, since there are management targets for controlling their populations.

Australian Capital Territory

The Nature Conservation Act 2014 requires that licences be obtained to take protected fauna or flora. These licences are administered by the Conservator of Flora and Fauna, within the ACT Parks and Conservation Service.

New South Wales

The National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 protects all native fauna (mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians) and flora. A licence is required to take protected fauna or flora. Regulation of non-native fauna is under the control of the Non-Indigenous Animals Act 1987. The Local Land Services Act 2013, Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016, and the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 also have provisions relevant to the harvesting of non-wood forest products. Management plans are in place for macropods (kangaroos), and plants (cut flowers and whole plants). The Forestry Act 2012 and Forestry Regulation 2022 provide specific provisions for the harvesting of non-wood forest products.

Northern Territory

The Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1976 and associated regulations require that a permit must be obtained to take or interfere with protected wildlife (fauna or flora) unless an exemption applies. 'Take' includes actions such as hunting, capturing, killing, or removing wildlife, while for flora it includes severing or destroying plants. Management plans are in place for cycads (Liddle 2009), crocodiles (Saalfeld et al. 2015; Clancy et al. 2024) and the magpie goose (Clancy 2020).

Queensland

The Nature Conservation Act 1992 is the principal legislation that provides for the protection of native flora and fauna. Appropriate authorisations or permits under the Act are required prior to any taking or interfering with protected flora and fauna, unless the activity is exempt. The Forestry Act 1959 provides for forest reservations and the management of forests, and the sale of state-owned forest products including timber and non-wood products. The Forestry Act 1959 applies to state forests, timber reserves, leasehold lands, reserves, public lands and certain freehold lands. Management plans are in place for macropods (kangaroos), crocodiles, and protected plants including sandalwood.

South Australia

The National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 provides the state's legislative framework for the conservation of wildlife and flora in their natural environment. A permit is needed to take any protected species, except where the relevant minister declares otherwise based on a threat to crops or property, or declares an open hunting season for protected animals of specified species. Management plans are in place for macropods (kangaroos).

Tasmania

Wildlife in Tasmania (defined as all living creatures except stock, dogs, cats, farmed animals and fish) is protected by the Wildlife Regulations Act 1999. Open season may be declared by the Minister for Environment, Parks and Heritage for particular species including wallabies, possums, deer, wild ducks and mutton-birds. Harvesting of tree ferns, is regulated through a Commonwealth management plan implemented under the Forest Practices Act 1985.

Victoria

In Victoria, wildlife (defined as vertebrate species Indigenous to Australia, some non-native game species, and terrestrial invertebrate animals that are listed under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988) is protected under the Wildlife Act 1975. A licence or authorisation is needed to take, destroy or disturb wildlife or flora listed as protected under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988. Management plans are in place for kangaroos.

Western Australia

The Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 and Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2018 provide for the conservation and protection of all native flora and fauna in Western Australia through a system of licensing for commercial use, area-specific and species-specific management, and monitoring. A management plan governs the commercial harvesting of protected flora and fauna in Western Australia. Management plans are in place for kangaroos, wildflowers and sandalwoods.

Non-wood forest products from forest-dwelling fauna include honey and other apiary products, meat and skins from kangaroos, possums, wallabies and feral animals, and crocodile eggs.

Honey and pollination services

Australia is one of the top ten honey producing countries in the world. Commercial honey production occurs in all states and territories, however, the bulk of production is concentrated in the eastern states and south-west Western Australia. New South Wales is Australia’s largest producer of commercial honey (DAFF 2024a). Apiary sites are generally located in forest or other wooded land on public and private tenure (Clarke and Le Feuvre 2024).

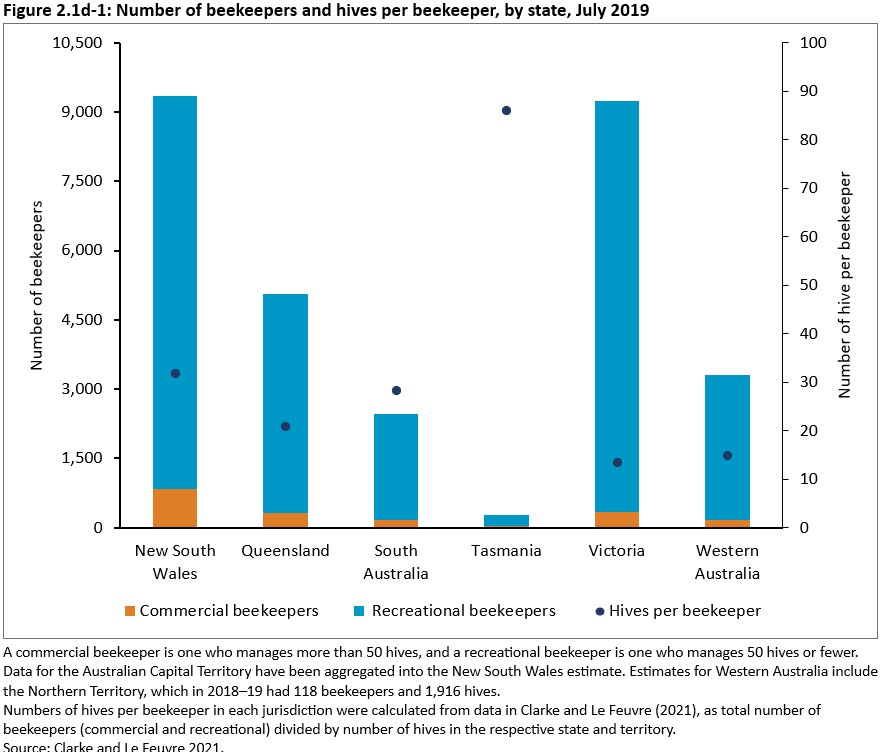

Honey is produced by commercial beekeepers (managing more than 50 hives) and recreational beekeepers (managing 50 hives or fewer). The number of commercial beekeepers increased from 1,280 in 2014–15 (van Dijk et al. 2016) to 1,868 in 2019 (Clarke and Le Feuvre 2021). In 2019, there were also 27,822 recreational beekeepers. Commercial and recreational beekeepers combined managed a total of 668,672 hives in 2019 (Figure 2.1d-1 and Table 2.1d-1). The number of hives per commercial beekeeper has increased from 156 in 1962 to 299 in 2018 (Clarke and Le Feuvre 2021).

In 2019, Tasmania had the fewest beekeepers of any state, but the highest average number of hives per beekeeper (86 hives). Victoria and New South Wales had the most beekeepers, yet very different hive densities: 13 hives per beekeeper in Victoria compared to 32 in New South Wales. The lowest average numbers of hives per beekeeper were reported in Victoria and Western Australia (Figure 2.1d-1 and Table 2.1d-1).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-1.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 2.1d-1.

Sustainable honey production and pollination services rely on the availability of healthy ecosystems. Forests play a critical role in supporting commercial pollination by providing essential floral resources (nectar and pollen) for honeybees, particularly during off-peak periods in the agricultural cycle. Trees also provide natural shelter for hives and serve as pesticide-free refuges. Hives are often placed in forests based on the availability of flowering tree and understorey resources, as well as in other types of vegetation where bees can forage (Donkersley 2019).

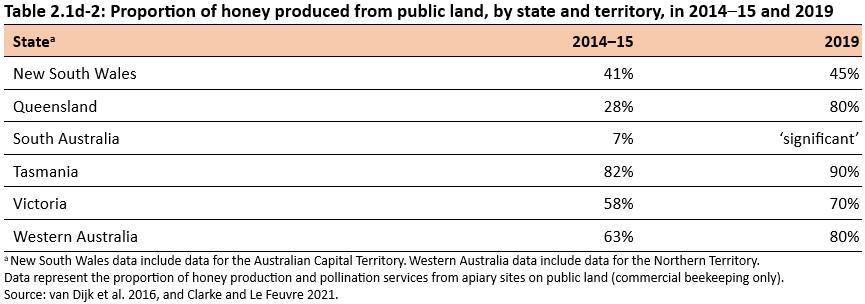

The proportion of honey produced on publicly managed lands (multiple-use public forests, nature conservations reserves, and other Crown land) varies by jurisdiction but is generally high (Table 2.1d-2). In 2019, publicly managed land accounted for 90% of Tasmanian honey production and 80% of Queensland’s honey production. In Queensland, this was a significant increase compared to the estimate in 2014–15 of 28%.

Typically, 70% of Australia’s honey is produced from native flora species (Spicer and McGaw 2020), mostly from eucalypts and related species (Keith and Briggs 1987; Somerville 2010). Leatherwood honey, known for its distinct flavour and texture, is produced from leatherwood (Eucryphia lucida) trees that occur only in Tasmania, predominantly in mature wet eucalypt forest and rainforest.

Pollination services provided by beekeeping activities are critical to Australia’s horticulture industry. Pollination by bees contributes between $0.62 and $1.73 billion to Australian agriculture each year (DAFF 2024a, 2024b). About 35% of all crops depend on pollinators, particularly honeybees (DAFF 2024a, 2024b). Almonds, apples, avocados, and blueberries entirely depend on bees, while cherries and macadamias are highly dependent on them (Clarke and Le Feuvre 2021; Gillespie et al. 2024).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Table 2.1d-2.

Potential threats to the sustainability of the honey industry include:

- restrictions on access to native flora due to land clearing for agriculture, forest dieback and degradation, bushfires and the conversion of multiple-use public forest to nature conservation reserve where apiaries may not be permitted (MIG and NFISC 2018)

- changing climate conditions affecting flowering patterns of forest species

- colony collapse disorder

- pests and disease such as the Varroa mite (DPI 2024a).

Native animal meat and skin products

Harvesting meat and skin products from native animals in most cases requires a permit and is largely restricted to species that are considered common.

Crocodile

The Australian crocodile industry is based on products from the saltwater or estuarine crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), and to a lesser extent, from freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni). The Australian saltwater crocodile industry, consisting of 21 operators across the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia, is anticipated to grow (Pattison et al. 2023).

The industry produces skins used in the manufacture of high-quality fashion items. The main importing countries are France, Singapore, Italy and Japan. The quantity of skins exported annually is reported in Indicator 6.1b.

As Australian saltwater crocodiles are listed in Appendix II of the Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the Australian Government Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water is responsible for annual reporting to CITES. Skins are tagged as part of a chain of custody process and exports require licensed crocodile farms and meat processors to have permits.

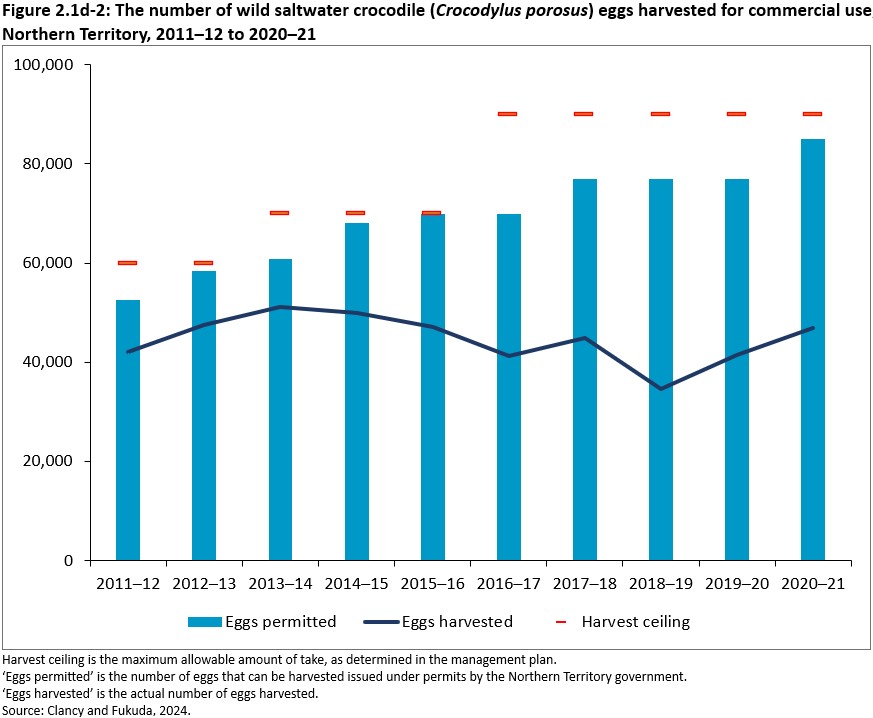

In the Northern Territory, production stock for crocodile farms comes from either captive-bred eggs or harvested wild saltwater crocodile eggs. Some crocodiles are bred in captivity, and their eggs and hatchlings are sold to farms to be grown out. Most production stock in the Northern Territory, however, are from the wild. Wild crocodile eggs are often sourced from mangrove forests and forested wetlands, including Melaleuca forests. From 2016 to 2021, the annual saltwater crocodile harvest limit was 90,000 eggs and 1,200 live crocodiles. This compares to 70,000 eggs from 2013 to 2015 and 60,000 eggs from 2011 to 2013 (Saalfeld et al. 2015; Clancy and Fukuda 2024). Since 2011, both the number of saltwater crocodile eggs permitted for harvest and the actual number harvested remained within the allowable harvest limit (Figure 2.1d-2).

The management and regulation of crocodile harvesting from the wild in the Northern Territory is administered through the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1976. The Northern Territory Department of Agriculture and Fisheries regulates both wild and farmed crocodiles under the Animal Protection Act 2018 and its associated regulations. Sustainable management of commercially harvested crocodiles including collection of eggs from the wild is regulated under the Wildlife Trade Management Plan Crocodile Farming in the Northern Territory 2021 - 2025. Crocodile farming is further regulated under the Livestock Act 2008, and the Meat Industries Act 1996 since crocodile meat is also harvested. The Livestock Act 2008 establishes requirements for crocodiles farming including disease surveillance, and the Meat Industries Act 1996 regulates abattoir licensing and ensures crocodile meat is safe for human consumption (Saalfeld et al. 2015).

In Queensland, crocodile production stock is primarily sourced from captive breeding, limited harvest of local wild crocodile eggs, and imported eggs and juveniles (hatchlings) from the Northern Territory. Crocodiles are protected under the Nature Conservation Act 1992, the Nature Conservation (Animals) Regulation 2020, the Nature Conservation (Estuarine Crocodile) Conservation Plan 2018 and the Queensland Crocodile Management Plan, and wild commercial egg harvesting is strictly regulated (DEHP 2017).

The crocodile farming industry in Western Australia is relatively small compared to the Northern Territory and Queensland (Pattison et al. 2023). Both saltwater and freshwater crocodiles are protected under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Commercial crocodile harvesting and live capture require permits and are regulated under the Wildlife Conservation Act 1950 and Wildlife Conservation Regulations 1970.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-2.

Kangaroo

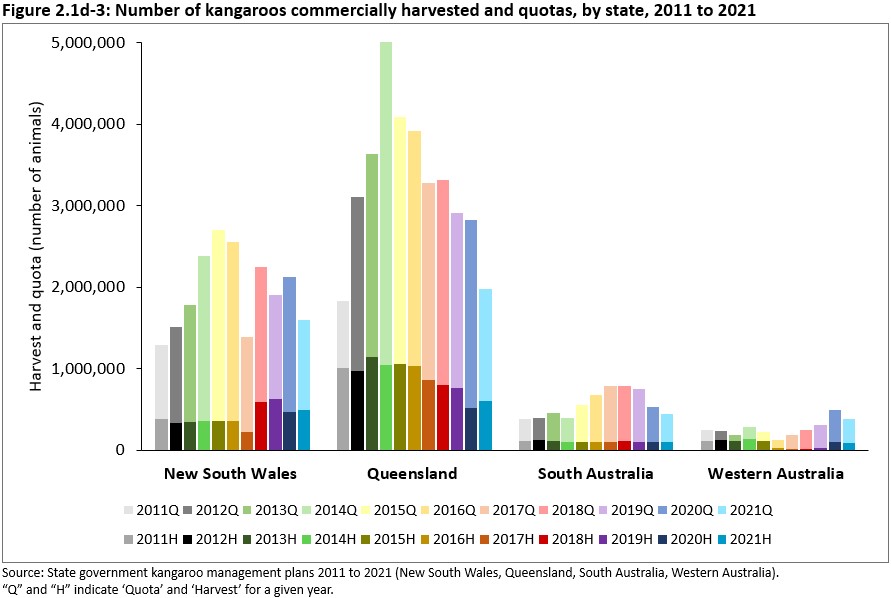

Australia’s kangaroo industry involves the commercial harvest of kangaroos for both meat and skin, with operations active in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia. Wildlife Trade Management Plans for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos are approved for each state under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. Long-term studies of wild kangaroo populations have found no evidence of population decline resulting from over 30 years of commercial harvesting. Annual harvest quotas based on population surveys are typically set at 15–20% of population estimates, however, actual harvest levels are usually much lower at around 3–5% of the total population (Figure 2.1d-3).

The Wildlife Trade Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in New South Wales 2022-26 details annual harvest quotas for relevant species. Species allowed for harvest are the common wallaroo (Osphranter robustus), eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus), red kangaroo (O. rufus) and western grey kangaroo (M. fuliginosus). The annual commercial harvest has only been 13%–33% of the quota since 2011 (Figure 2.1d-3). Note that this figure does not include kangaroos culled under New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service non-commercial licence-to-harm permits.

In Queensland, the Nature Conservation (Macropod) Conservation Plan 2017 regulates macropod harvesting, under the Nature Conservation Act 1992. The Act specifies the use of a harvest period and other conditions for the taking of macropods. Species allowed for harvest are the common wallaroo, eastern grey kangaroo, and red kangaroo. The annual commercial harvest has been 18–56% of the quota since 2011 (Figure 2.1d-3).

In South Australia, all kangaroo species are protected under the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 and associated regulations. In accordance with the South Australian Commercial Kangaroo Management Plan 2020–2024 (now updated to a 2025–2029 plan), harvest quotas are set annually for each species. Species allowed for harvest are red kangaroo, western grey kangaroo (which includes both the mainland subspecies M. fuliginosus melanops and the Kangaroo Island subspecies M. fuliginosus fuliginosus), eastern grey kangaroo, common wallaroo, and Tammar wallaby, M. eugenii. Prior to 2020, harvest was only allowed for red kangaroo, eastern grey kangaroo and common wallaroo. The annual commercial harvest has only been 13–31% of the quota since 2011 (Figure 2.1d-3).

In Victoria, commercial harvesting of eastern and western grey kangaroo has been allowed since 1 October 2019 under the Victorian Kangaroo Harvest Management Plan. The latest version is the Victorian Kangaroo Harvest Management Plan 2024–2028. Kangaroos can also be culled under an Authority to Control Wildlife permit for agricultural damage mitigation purposes. The total annual quota for harvesting and culling kangaroos is set at 10% of the total population.

In Western Australia, the taking of kangaroos from private land and Crown land is regulated under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. Under the Act, the Biodiversity Conservation Regulations 2018 provide licensing arrangements for taking, processing, dealing, importing and exporting kangaroos for commercial purposes. The Management Plan for the Commercial Harvest of Kangaroos in Western Australia 2024-2028 further regulates the commercial kangaroo industry, including the export of products. Two species, the red kangaroo and western grey kangaroo are commercially harvested in Western Australia. The annual commercial harvest has been 8–64% of the quota since (Figure 2.1d-3).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-3.

Brushtail possum, Bennett’s wallaby and rufous wallaby

In Tasmania, common brushtail possums (Trichosurus vulpecula), Bennett’s wallaby (Notamacropus rufogriseus) and rufous wallaby or Tasmanian pademelon (Thylogale billardierii) are scheduled as ‘partly protected wildlife’ under the Nature Conservation Act 2002 and Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulations 2021. These regulations are administered by the Department of Natural Resources and Environment.

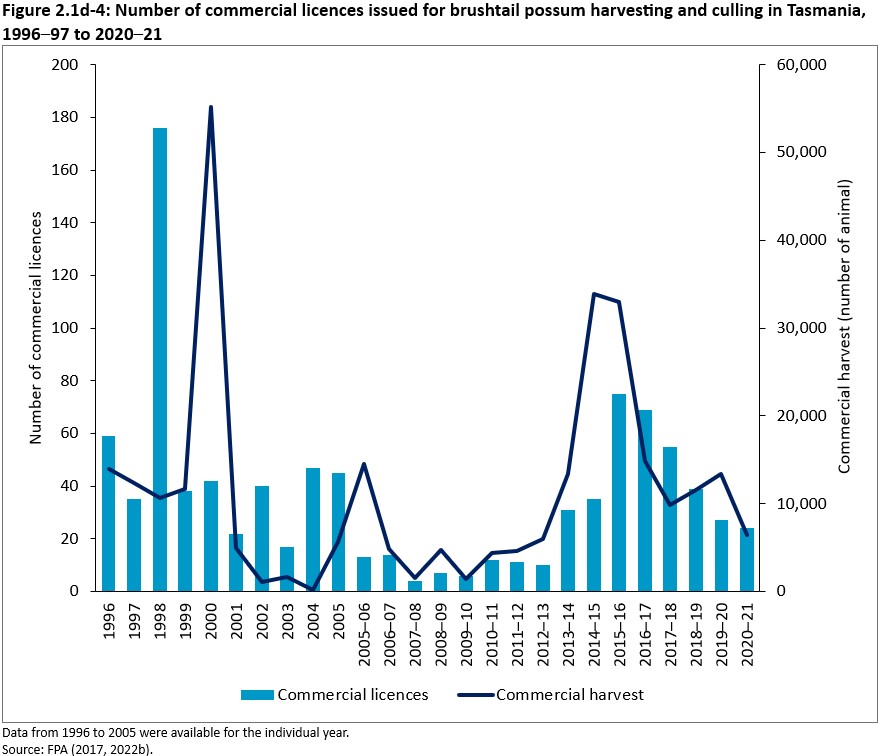

Common brushtail possums are permitted to be harvested for skins and fur in accordance with a Commonwealth-approved management plan (DPIPWE 2015) and their products exported overseas. The commercial harvest of Brushtail possums was authorised under commercial brushtail possum permits.

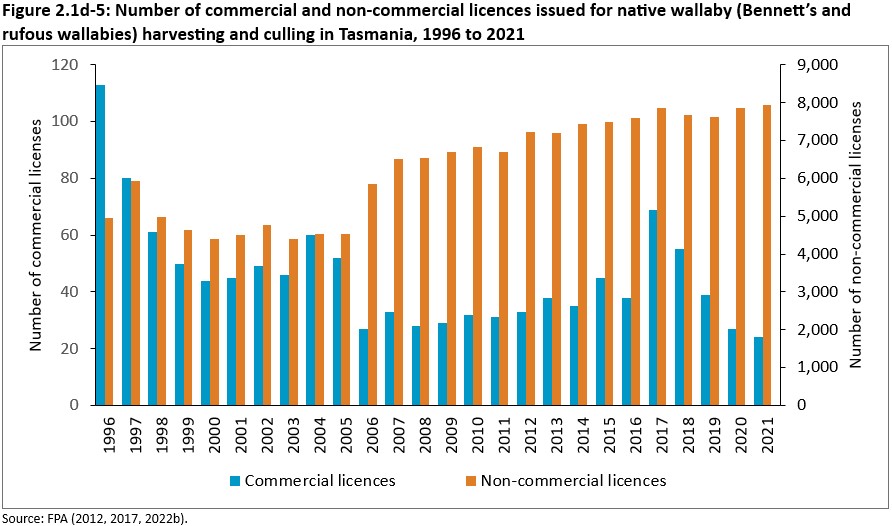

Commercial harvesting of Bennett’s wallaby and rufous wallaby for meat and skin products is also permitted, however, only for use within Australia.

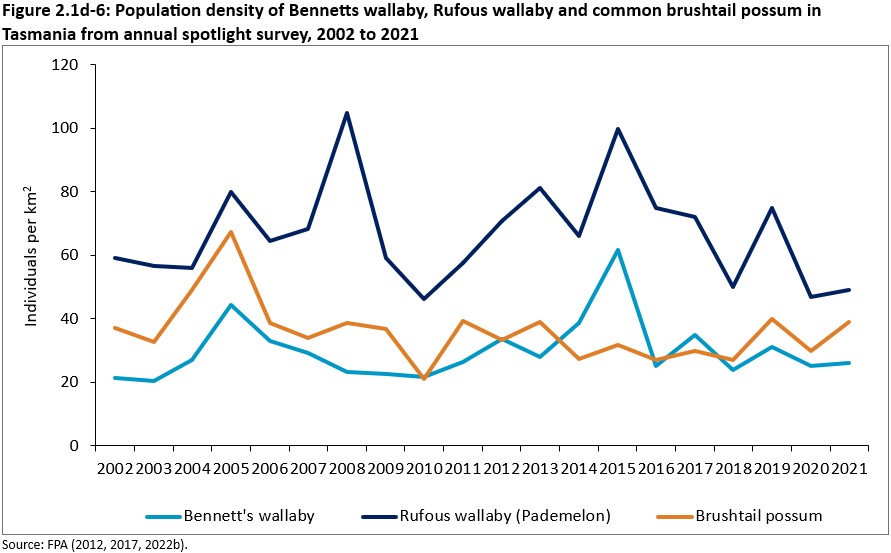

Browsing of seedlings by common brushtail possums and Bennett’s and rufous wallabies is a major risk during the establishment of eucalypt plantations. Bark stripping by wallabies is prevalent in commercial pine plantations (see Indicator 3.1a) and brushtail possums and wallabies can cause significant damage to agricultural crops (FPA 2022). Landholders can procure a Crop Protection Permit that authorises the taking of brushtail possums, Bennett’s and rufous wallabies causing damage to crop in primary production areas. Non-commercial culling of these species may occur under a property protection permit.

Between 2015-16 and 2020-21, the commercial harvest of brushtail possums declined from over 30,000 per year to less than 10,000 per year (Figure 2.1d-4).

The number of commercial licences issued for wallabies in 2021 was lower than in 2016, whereas the number of non-commercial licences remained relatively steady (Figure 2.1d-5).

Annual spotlight surveys show that wallaby and brushtail possum populations have remained stable over time, indicating that harvesting and culling is within sustainable levels (Figure 2.1d-6).

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-4.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-5.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-6.

Mud crab

The two species of mud crabs occurring in Australian waters are the giant mud crab (Scylla serrata) and the orange mud crab (S. olivacea). Mud crabs generally inhabit sheltered estuaries and the tidal reaches of rivers and creeks among mangrove forests. Commercial mud crab fisheries and stock in selected regions across New South Wales, the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia have been determined to be at sustainable levels (FRDC 2023). Details on the commercial catch of mud crabs in 2013 to 2021 is presented in Indicator 6.1b.

Regulatory frameworks are in place to ensure sustainable levels of harvesting across the states and territories. For example, Queensland has a male-only harvest policy and a minimum legal size limit for male crab harvesting, aimed to maximise the number of females that survive to spawn and ensuring male contribution to breeding. Several no-take zones are also enforced to provide additional protection for the species (FRDC 2023).

Introduced animal products

Introduced animal species inhabiting forests, such as pigs, goats, water buffalo and deer, are also harvested for meat and skins, or antlers. Many of these animals pose threats to agricultural and forestry crops, as well as native biodiversity. Harvesting rates for introduced species are usually determined by forest management considerations rather than ecological sustainability criteria.

Deer

Fallow deer (Dama dama) are recognised as a game resource in Tasmania and as such are listed as ‘partly protected wildlife’ under the Nature Conservation (Wildlife) Regulations 2021. During the reporting period, the selling or trading of venison from wild shot deer was not permitted. Fallow deer may be hunted at certain times of the year under a recreational hunting licence. Property protection permits can also be applied for by farmers and forest managers to mitigate damage by deer browsing and bark-stripping (FPA 2022b).

In New South Wales, fallow (Dama dama), rusa (Rusa timorensis), red (Cervus elaphus), sambar (Cervus unicolor) and chital deer (Axis axis), are an expanding group of pest species found in most regions and are priority pests, as well as a hunting resources. The Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development administrates recreational deer hunting. Local Land Services work with land managers and Government agencies such as the New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service to control feral deer populations, protect land and livestock and minimise threats to public safety. Local Land Services also work with regional pest animal committees and the community to develop regional strategic pest animal management plans. These plans support the regional implementation of the New South Wales Biosecurity Act 2015. In New South Wales, recreational hunting is generally permitted in declared state forests all year round.

In Victoria, recreational deer hunting is also generally permitted all year round. The total number of deer harvested in 2021 was estimated at 118,900 animals (Moloney and Flesch 2022). Prior to 2020, the estimated Victorian deer harvest had been increasing annually at a rate of 17% (Moloney et al., 2022). Sambar deer was the most harvested deer species in 2021, followed by fallow deer and red deer (Moloney and Flesch 2022).

Goat

Feral goats (Capra hircus) are declared agricultural and environmental pests in Queensland under the Rural Lands Protection Act 1985 and classified as a restricted invasive animal under the Biodiversity Act 2014 (DAF 2023); in Victoria under the Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994 (DEECA 2025); in South Australia under the Landscape South Australia Act 2019 (PIRSA 2021); and in Western Australia under the Biosecurity and Agriculture Management Act 2007 (DPIRD 2024). In New South Wales, feral goat is considered a priority pest animal under the Biosecurity Act 2015.

Feral goats are commercially harvested for meat and hides in New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia (Forsyth et al. 2009; DEEDI 2010; Khairo et al. 2013; DPI 2020, 2021), contributing to regional economies and pest management objectives. The majority of feral goat products are exported abroad (DAFF 2023). Harvest volume and value are presented in Indicator 6.1b.

New South Wales has the largest population of rangeland goats in Australia, however most of the processing is done in Queensland and Victoria (DPI 2020, 2021). Feral goat control in New South Wales is primarily done through commercial harvesting via mustering. Feral goats captured and moved must comply with National Livestock Identification System requirements. Local Land Services provides advice and support for feral goat management in New South Wales. Regional Strategic Pest Animal Management Plans that outline the recommended control methods are established for Local Land Services regions.

Plant-based non-wood forest products include seeds and wildflowers, tree ferns, and aromatic oils from sandalwood and tea tree. Quantitative assessment to determine harvest sustainability of these non-wood forest products were limited by data availability.

Sandalwood

Native Australian sandalwood species include Santalum album, S. lanceolatum, S. murrayanum, S. obtusifolium and S. spicatum. Almost all native sandalwood products are currently sourced from Western Australian sandalwood (S. spicatum), with a small proportion sourced from northern sandalwood (S. lanceolatum) in northern Queensland.

The wood is harvested and used for carvings, ground to produce incense, and the heartwood oil is extracted for cosmetics, aromatherapy and pharmaceuticals. Production volumes and values of sandalwood, including sandalwood oil, are reported in Indicator 2.1c and Indicator 6.1b.

Wild populations of S. spicatum and S. lanceolatum have significantly declined due to cumulative impacts associated with pests, grazing, over-harvesting, altered fire regimes and climate change (Brunton et al. 2021; McLellan et al. 2021). Further, S. spicatum populations have been impacted by declining numbers of boodies (burrowing bettongs, Bettongia lesueur) and woylies (brush-tailed bettongs, Bettongia penicillata) which perform critical natural seed dispersal functions.

Approximately 21,000 hectares of S. spicatum plantations have been established in central-south Western Australia since the 1990s (Bush et al. 2018), of which the Western Australia Forest Products Commission manages about 6,000 hectares (FPC 2024). The S. spicatum sandalwood plantations are currently being harvested and re-planted (Thomson 2020). There are no known commercial plantations established for S. lanceolatum. Private investment established more than 17,000 ha of Indian sandalwood S. album plantations in northern Australia (Stephens et al. 2020), some of which is being harvested now.

Western Australia is the largest producer of sandalwood from S. spicatum harvested almost exclusively from natural stands. Western Australian sandalwood is not listed as either threatened or priority flora, but under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 all native flora including any part of it, is protected. The taking of native flora, including for the sale from private property, requires a licence that is issued by the Western Australia Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions. Commercial harvesting of wild sandalwood on Crown land is controlled under the Forest Products Act 2000 and the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. The Sandalwood Biodiversity Management Programme provides for the protection, conservation and sustainable management of wild sandalwood on both Crown and private lands (DBCA 2023).

The Western Australia Forest Products Commission is responsible for the commercial harvesting, regeneration and sale of wild sandalwood from Crown land. Wild sandalwood harvested by the Western Australia Forest Products Commission is certified to the international standard for Environmental Management Systems (EMS ISO 14001:2015) as well as Chain of Custody certification under the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Standard (PEFC ST) 2002:2020 (FPC 2016-22).

In Queensland, northern sandalwood (S. lanceolatum) is listed as a special least concern plant under the Nature Conservation (Plants) Regulation 2020. Under the Nature Conservation Act 1992, northern sandalwood harvesting requires a protected plant harvesting licence and must satisfy certain legal requirements.

Tree fern

Tree ferns grow in height at a rate of 3.5–5.0 cm per year and can reach reproductive maturity in about 30 years (FPA 2017), at which they are likely to be a harvestable size. In Australia, they are harvested from forests for domestic and export markets primarily as ornamental plants. They are also used for floristry and other horticultural applications including as plant pots and mulch.

Numerous species of tree ferns (across several genera including Dicksonia and Cyathea) occur in Australia, but only certain species are allowed to be harvested. Tree fern products available on the market are largely soft tree fern (Dicksonia antarctica), also known as man fern, sourced from Tasmania. Soft tree fern naturally occurs in all states and territories except the Northern Territory and Western Australia (CHAH 2006), however, in states other than Tasmania, harvesting is strictly regulated.

Harvest of protected tree fern species is prohibited. Protected tree fern species include Cyathea exilis, which is endemic to Cape York Peninsula and listed as Endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act), and Alsophila cunninghamii (syn. Cyathea cunninghamii), listed as Endangered under Tasmania’s Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 and as Critically Endangered under Victoria’s Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988.

The commercial export of tree ferns requires a permit and is regulated under the EPBC Act, for which the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water is responsible. Under the Commonwealth Export Control Act 2020 for which the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry is responsible, the export of tree ferns may require inspection for compliance and certification by an accredited plant export Authorised Officer. The rules for international export of tree ferns are set out in the Commonwealth Export Control (Plants and Plant Products) Rules 2021.

In Tasmania, of the five native tree fern species occurring in the state (D. antarctica, Cyathea australis, C. cunninghamii, C. x marcescens and Todea barbara), only D. antarctica may be harvested. Harvest is regulated in accordance with the Tasmanian Tree Fern Management Plan 2017 (FPA 2017, revised in FPA 2022a) and can only be harvested under a certified forest practices plan from areas in which the tree ferns would otherwise be lost/destroyed during regeneration burns following timber harvesting. All harvested tree ferns must be sold with a Tasmanian tree fern tag issued by Tasmania’s Forest Practices Authority. These tags must remain on the stems to ensure that the origin can be tracked to approved harvest areas. Tasmania tree fern harvest volume and values are presented in Indicator 6.1b.

The number of soft tree ferns (D. antarctica) occurring in Tasmania’s forests, as at 2021, was estimated as 130–165 million individual trunks (FPA 2022b). Most of Tasmania’s harvested tree ferns are exported internationally, including to Europe (FPA 2022a). Available tree fern resources, rates of regeneration and growth rates indicate that current harvest levels are within sustainable yields. Integration of tree fern harvesting with timber harvest operations undertaken under Tasmania's forest practices system, provides an opportunity for efficient resource utilisation.

The primary source of tree ferns in Victoria is through salvage during harvesting operations in pine plantations. In Victoria, D. antarctica is protected under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, and its harvest must comply with the conditions in a permit administered by the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action and local government controls under the Planning and Environment Act 1987, and other prescriptions such as the Code of Practice for Timber Production 2014 (Revision No. 2) and the Victorian Tree-fern Management Plan - December 2001.

In New South Wales, tree ferns of Dicksonia and Cyathea species are protected under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 but may be harvested from the wild through licensing, tagging and regulatory tools, such as the Whole Plant Sustainable Management Plan 2023–2027. Farm-produced materials must also be tagged.

Wildflowers

Commercial harvesting of native cut flowers and foliage flora is a significant industry and includes seed harvesting (primarily for propagation and revegetation purposes) and collection of nuts, cones and woody stems for the craft market. Australia’s wildflowers export volumes and values are presented in Indicator 6.1b.

Wildflower industries in Western Australia are based on a combination of horticulture and native resources from forest and other wooded land on public and private tenure. A substantial proportion of wildflowers harvested in Western Australia are exported (DEC 2013). The Western Australia Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions issues licences and authorisations under the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 for the take of flora, including for commercial harvest. The Management of Commercial Harvesting of Flora in Western Australia 2018-2023 plan (updated 2023–2028) guides commercial harvesting on both private and public land, including the export of plant material.

In New South Wales, the Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water works with industry and other stakeholders to manage the use of cut flowers and foliage from native plants through licensing and regulatory tools, such as the Cut-flower Sustainable Management Plan 2018–2022 (updated 2023–2027). This plan describes the licensing framework and processes for regulating and monitoring protected plant species that are harvested from the wild or artificially propagated for the cut-flower industry.

Queensland’s Department of the Environment, Tourism, Science and Innovation can issue licences required to harvest native plants listed as threatened species and near-threatened species under the Nature Conservation Act 1992 or least concern species listed in schedule 2 of the Nature Conservation (Plants) Regulation 2020 from both public and private lands. Licences apply to the harvest of whole restricted plants from the wild, or the harvest of restricted plant parts from the wild in excess of the limits set in the ‘Code of Practice for the harvest and use of protected plants under an authority’.

A permit is required to take native plants from public land in Victoria that are classified as protected flora under Victoria’s Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988. A permit is not required in Victoria for flora taken from private land (other than land which is part of the critical habitat for the flora) by a person who is the owner of the land; is leasing the land; or has been given permission by the landowner or the lessee and has not taken the flora for commercial purposes. For the collection of protected flora from public land for non-commercial purposes, a permit application must be lodged with the appropriate Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action regional office.

Forest seeds

Forest seeds are used in native forest regeneration, plantation establishment, propagating nursery stock, revegetation and environmental plantings. Seed collection from forests is regulated and reported by relevant public authorities.

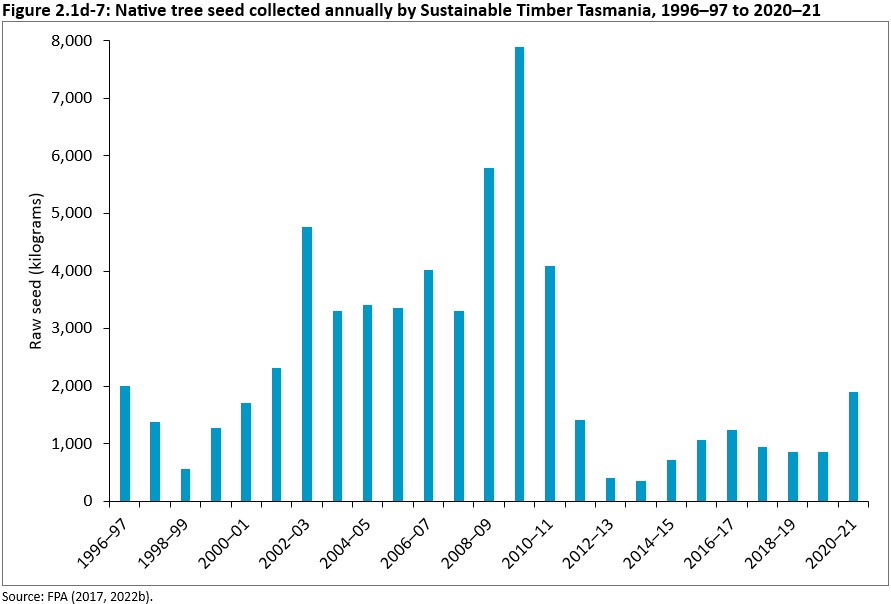

In Tasmania, seeds are collected by Sustainable Timber Tasmania and private collectors largely for use in native forest regeneration, propagating nursery stock and the establishment of plantations. As a standard practice, seed weight, origin, site details and germination capacity data for the seeds harvested are recorded. During 2016–17 to 2020–21, Sustainable Timber Tasmania collected a total of 5,792 kg of native tree seeds, which was 32% higher than seed volumes collected during 2011–12 to 2015–16 (Figure 2.1d-7).

The Forestry Corporation of New South Wales (FCNSW) collects seed to grow seedlings for hardwood timber plantations. FCNSW also recently commenced a seed collection program to ensure future forest regeneration and resilience for native obligate seeder species including alpine ash (Eucalyptus delegatensis) and white ash (E. fraxinoides). Victoria’s Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action also undertakes seed collection for forest regeneration activities, with 3,268 kilograms of seed collected in 2020–21.

Click here for a Microsoft Excel workbook of the data for Figure 2.1d-7.

Essential oils

High-value non-wood forest products from plants include tea tree oil, which is derived through the steam distillation of Melaleuca alternifolia leaves and branches. Tea tree oil has antiseptic and anti-inflammatory properties and is widely used in topical treatments to treat fungal, bacterial and viral infections, bruises and skin allergies. Tea tree oil is used in healthcare, cosmetic, pharmaceutical, veterinary and industrial products (DAWE 2017; AgriFutures Australia 2018). Export volumes and values of tea tree oil are presented in Indicator 6.1b.

In response to increasing global demand for tea tree oil during the 1980s, tea tree oil production in Australia expanded rapidly and moved from a reliance on harvesting in native stands to production in plantations. Tea tree plantations are largely found in northern New South Wales and Queensland.

Native bush food

Many of Australia’s native bush foods such as lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora), finger lime (Citrus australasica), Kakadu plum (Terminalia ferdinandiana) and quandong (Santalum acuminatum) are highly nutritious or have unique medicinal properties. Some have gained popularity across gastronomic and pharmaceutical industries nationally and globally. Many are forest-dwelling and thus considered non-wood forest products.

At least 6,500 plant species are known as native bush foods, however, only 13 have been effectively developed and grown commercially to date. They are lemon myrtle (B. citriodora), finger lime (C. australasica), Kakadu plum (T. ferdinandiana), wattle (Acacia spp.), Davidson’s plum (Davidsonia spp.), mountain pepper (Tasmannia spp.), anise myrtle (Syzygium anisatum), riberry (Syzygium leuhmanii), lemon aspen (Acronychia spp.), desert lime (C. glauca), quandong (S. acuminatum), muntries (Kunzea pomifera), and bush tomato (Solanum centrale). Note that macadamia is not included in this list because it is considered as horticulture, rather than a non-wood forest product. Estimated values of bush food industries are presented in Indicator 6.1b.

Most native bush food is still wild harvested, largely from Indigenous managed land and Crown land. Approval to undertake a Wildlife Trade Operation is required for the taking of certain native wildlife specimens, so harvesting native bush food from the wild requires government permits. Bush food plantations, such as for lemon myrtle, have been established in Australia and overseas. Plantations of Kakadu plum have been established in the Northern Territory and in Western Australia, mostly on Indigenous land (Gorman et al. 2016). Finger lime orchards, varying from 100 to over 2,000 trees, are predominantly established on the east coast of Australia and have expanded into Western Australia (Glover et al. 2022).

Indigenous people use native forest-dwelling plants and animals for foods, medicines, fibres, tools, dyes, pigments, and weaving. Non-wood forest products are an integral part of culture, sustenance and livelihoods.

Native bush foods utilised by Indigenous people include a wide range of plant and animal products such as honey grevillea, honey ants, bush tomato, bush sweet potato, bush carrots, bush passionfruit, lemon myrtle, quandong, daisy yam and bush seeds. The native bush food industry offers income diversification opportunities for Indigenous people and communities.

Kakadu plum plays a key role in the social and economic lives of Indigenous communities in northern Australia. Fruit is harvested from wild trees, usually from publicly owned land under a permit system and sold on the market. An assessment of demand relative to the abundance of the tree and quantity of fruit produced suggests that currently the risk of widespread, uniform over-harvest is low (Gorman et al. 2016). However, there is a risk of localised overharvest at accessible high-density sites (Whitehead et al. 2006). The Northern Australia Aboriginal Kakadu Plum Alliance (NAAKPA) aims to provide stability and reliability to the Kakadu plum supply chain. In the 2018–19 season, NAAKPA harvested more than 20 tonnes of Kakadu plum, with a farm gate value of $650,000 (Cutting et al. 2022). Harvest and export of Kakadu plum including their extracts, such as powder or puree and a range of other bushfood species requires Wildlife Trade Operation approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth).

Yerrabingin (New South Wales), Maningrida Wild Foods (Northern Territory), IndigiGrow (New South Wales), NAAKPA (Western Australia and Northern Territory), and Mayi Harvests (Western Australia), are examples of Aboriginal owned and managed organisations established to advocate for First Nations representation in the native bush food industry. Australian Native Food and Botanicals is the national peak body which represents all interests in the growing Australian native food industry and aims to support ethical engagement with Traditional Owners.

A bush food project in Kakadu National Park funded through the National Environmental Science Program has been initiated to identify native bush food diversity and abundance and inform their management. Examples of Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs) with a focus on native bushfood are Ngurra Kayanta IPA, and Ngururrpa IPA in Western Australia.

Many non-wood forest products are also used in traditional health and medicinal practices, and cultural ceremonies (Thompson et al. 2019; Turpin et al. 2022). For example, sandalwood was traditionally used to treat various ailments and burnt during ceremonies. ‘Sandalwood Dreaming’ is an initiative of Australia’s Reconciliation Action Plans to engage Indigenous-owned businesses and traditional owners to plant sandalwood seed and harvest dead sandalwood in Western Australia (FPC 2024). Indigenous sandalwood businesses, such as Dutjahn Sandalwood Oils and Marnta Sandalwood, have been established to ensure Traditional Owners receive a fair and equitable share from the commercial utilisation of the species.

Further information

Downloads

Indicator 2.1d: Annual removal of non-wood forest products compared to the level determined to be sustainable (2025) PDF [0.5 MB]

Tabular data for Indicator 2.1d - Microsoft Excel workbook [0.2 MB]