2021–22 to 2023–24

Recent farm performance

- An estimated 21% of Australian farm businesses are classified as broadacre cropping farms (18,000 farms), of which 9,300 were specialist cropping farms and a further 8,700 produced a mix of cropping and livestock ( see Methodology).

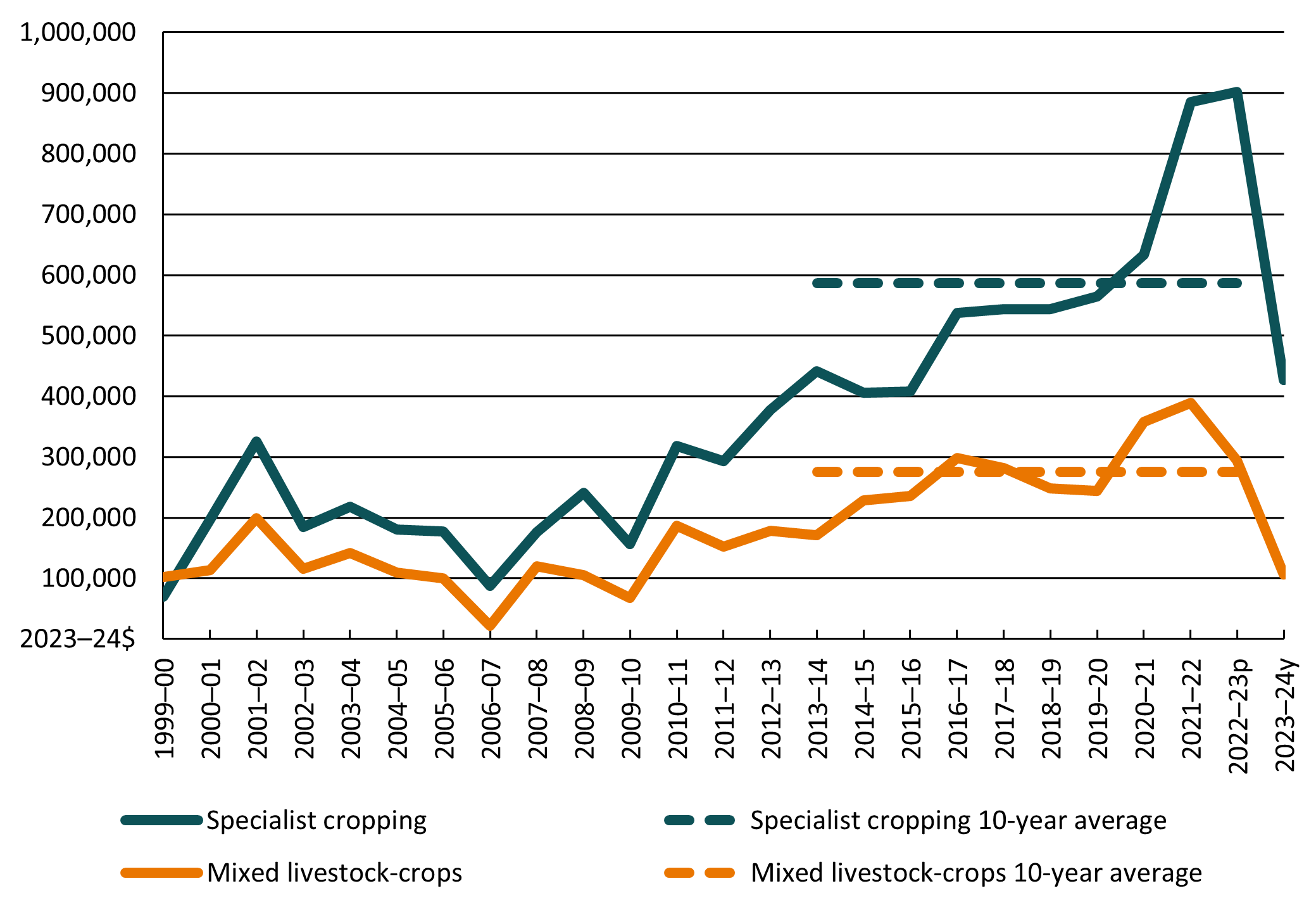

- Farm incomes for cropping farms are estimated to have fallen in 2023–24 because of lower grain prices and reductions in winter crop production in some areas.

- At the national level, average farm cash income for specialist cropping farms is estimated to have decreased by 53% in 2023–24 to $427,000 per farm. This estimate is 27% below the average in real terms (see Methodology) for the 10 years to 2022–23 (Figure 1).

- For mixed livestock-crops farms, average farm cash income is estimated to have decreased by 64% in 2023–24 to $106,000 per farm. This estimate is 61% below the average in real terms for the 10 years to 2022–23. Incomes for mixed livestock-crops farms were significantly affected by lower prices for cattle and sheep in 2023–24.

The PowerBI dashboard may not meet accessibility requirements. For information about the contents of these dashboards contact ABARES.

Figure 1 Farm cash income, cropping farms, Australia, 1999–2000 to 2023–24

Notes: p Preliminary. y Projection. All values are expressed in 2023-24 dollars.

Source: ABARES Australian Agricultural and Grazing Industries Survey

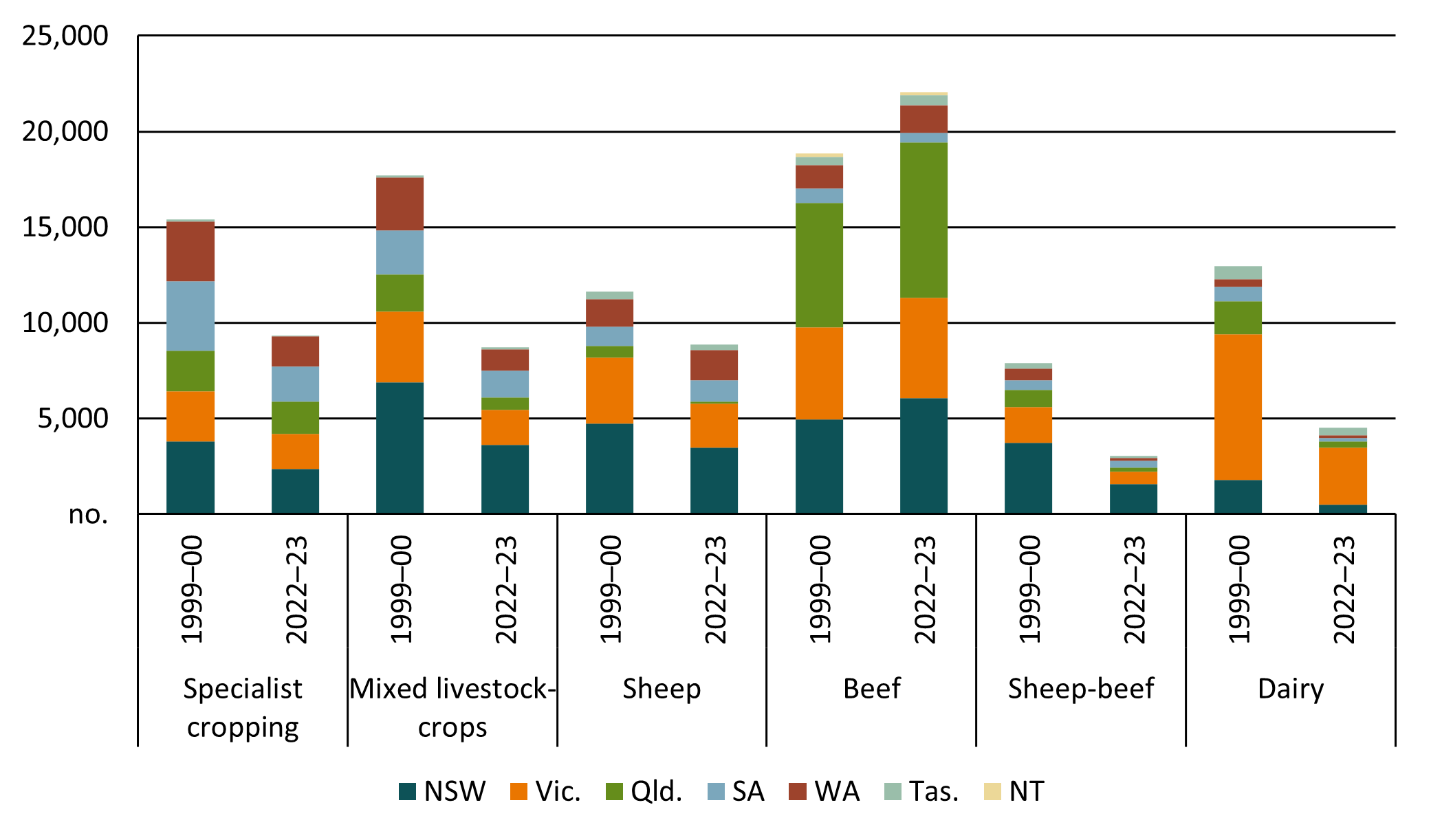

Changes in farm numbers

- The number of broadacre and dairy farms in Australia declined by around 33% from 1999–2000 to around 56,500 farms in 2022–23. The number of specialist cropping farms declined by 40% while the number of mixed livestock-crops farms declined by 51% (Figure 2).

- By state, the largest declines in the number of specialist cropping farms occurred in South Australia (49%), Western Australia (50%) and New South Wales (37%). The largest declines in the number of mixed livestock-crops farms occurred in New South Wales (48%), Victoria (50%) and Western Australia (60%).

- Despite declines in the number of farms, there was shift toward greater specialisation, with relatively more specialist cropping farms and fewer mixed livestock-crops farms in all states except South Australia where there was a small shift away from specialist cropping farms.

Figure 2 Change in number of farms, by industry and state

Changes in enterprise mix, receipts and costs

Specialist cropping farms

- Total cash receipts for specialist cropping farms increased at an annual average rate of 5.1% a year over the period from 1999–2000 to 2022–23.

- Specialist cropping farms became more crop intensive over the period, with total crop receipts contributing around 90% of total cash receipts in 2022–23, compared with 75% in 1999–2000.

- Although wheat remains the dominant crop, specialist cropping farms have shifted toward producing a more diversified mix of crops with increases in the share of oilseeds and barley in total crop receipts.

- Total cash costs for specialist cropping farms increased at an annual average rate of 4.4% a year over the period from 1999–2000 to 2022–23.

- As specialist cropping farms became more crop intensive there were increases in the proportion of total cash costs spent on fertiliser and crop and pasture chemicals. In 2022–23, fertiliser accounted for around 20% of total cash costs and crop and pasture chemicals accounted for 17%. In 1999–2000 these shares were 13% for fertiliser and 12% for crop and pasture chemicals.

- Despite strong increases in total cash costs in recent years, the ratio of total cash receipts to total cash costs has improved over the longer term at an annual average rate of 0.7% a year, reflecting improvements in farm productivity.

Mixed livestock-crops farms

- Total cash receipts for mixed livestock-crops farms increased at an annual average rate of 3.3% a year over the period from 1999–2000 to 2022–23.

- Only small changes in the enterprise mix on mixed livestock-crops farms was observed over the period, with an increase in the share of receipts from crops, sheep and lambs and a reduction in the share of receipts from beef cattle. As with specialist cropping farms, the share of receipts from barley and oilseeds increased but wheat remains the dominant crop.

- Total cash costs for mixed livestock-crops farms increased at an annual average rate of 2.8% a year over the period from 1999–2000 to 2022–23.

- Increases in expenditure on fertiliser and crop and pasture chemicals were not as pronounced for mixed livestock-crops farms as for specialist cropping farms. Fertiliser expenditure for mixed livestock-crops increased at an annual average rate of 4.3%, while crop and pasture chemicals increased at a rate of 4.1%.

- The ratio of total cash receipts to total cash costs has improved slightly over the longer term at an annual average rate of 0.4% a year, reflecting small improvements in farm productivity.

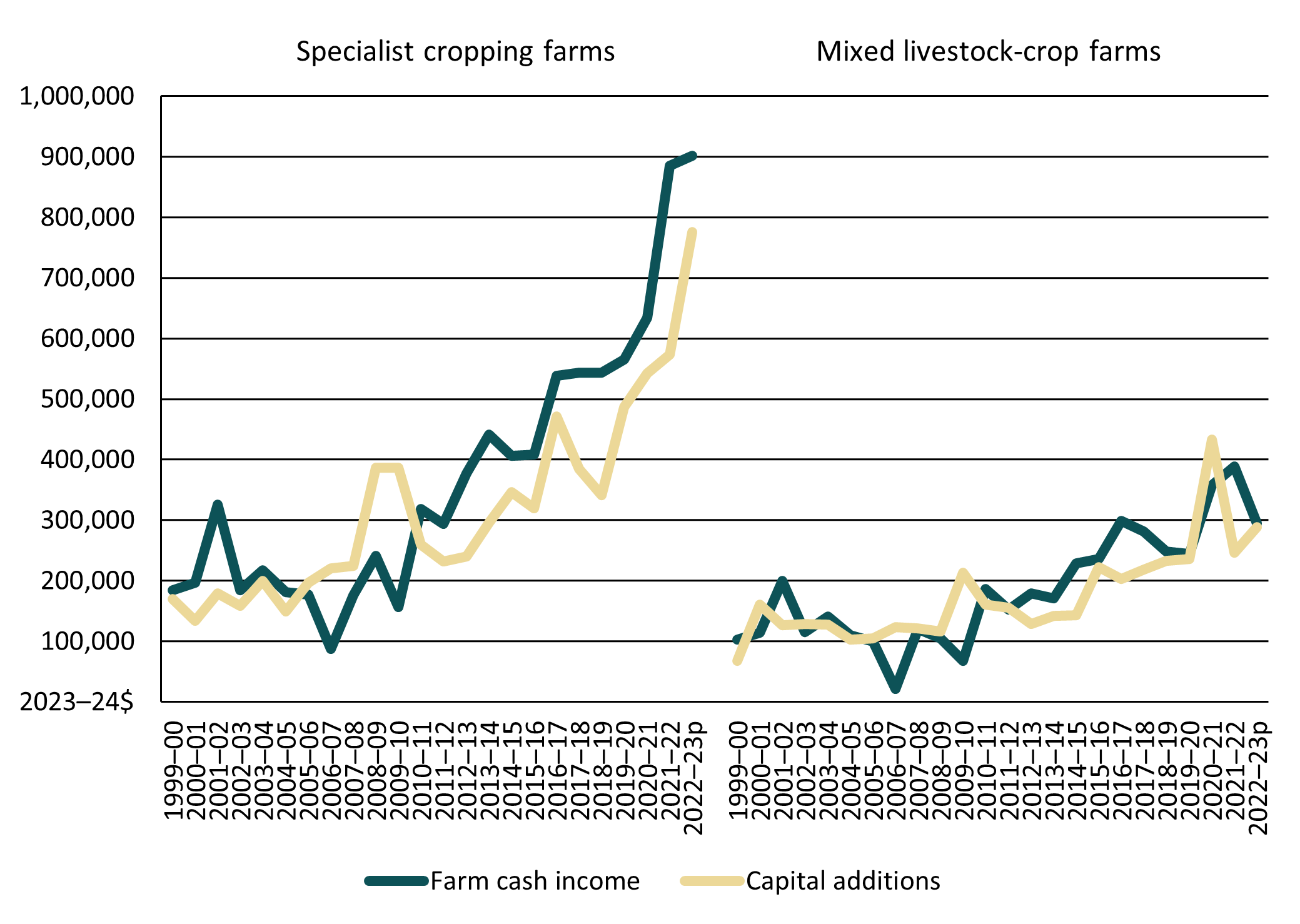

- Sustained industry growth and resilience relies on businesses continually investing to improve efficiency, increase scale or replace older capital items with newer and more efficient technologies.

- Over the past decade, the amount invested each year by livestock farms making capital additions fluctuated broadly in line with movements in farm cash incomes. That is, spending on new capital tended to rise and fall in line with changes in farm profitability (Figure 3).

- In high income years many farmers invest surplus funds in farm development or purchasing capital equipment. Increases in incomes also provide additional funds to invest and/or stronger cashflows to service additional debt. However, the level of investment varies by farm size, with smaller farms often increasing their holdings of liquid assets in high income years rather than reinvesting back into their farm business.

Figure 3 Farm cash income and capital additions, cropping farms, 1999–2000 to 2022–23

average per farm

Source: ABARES Australian Agricultural and Grazing Industries Survey

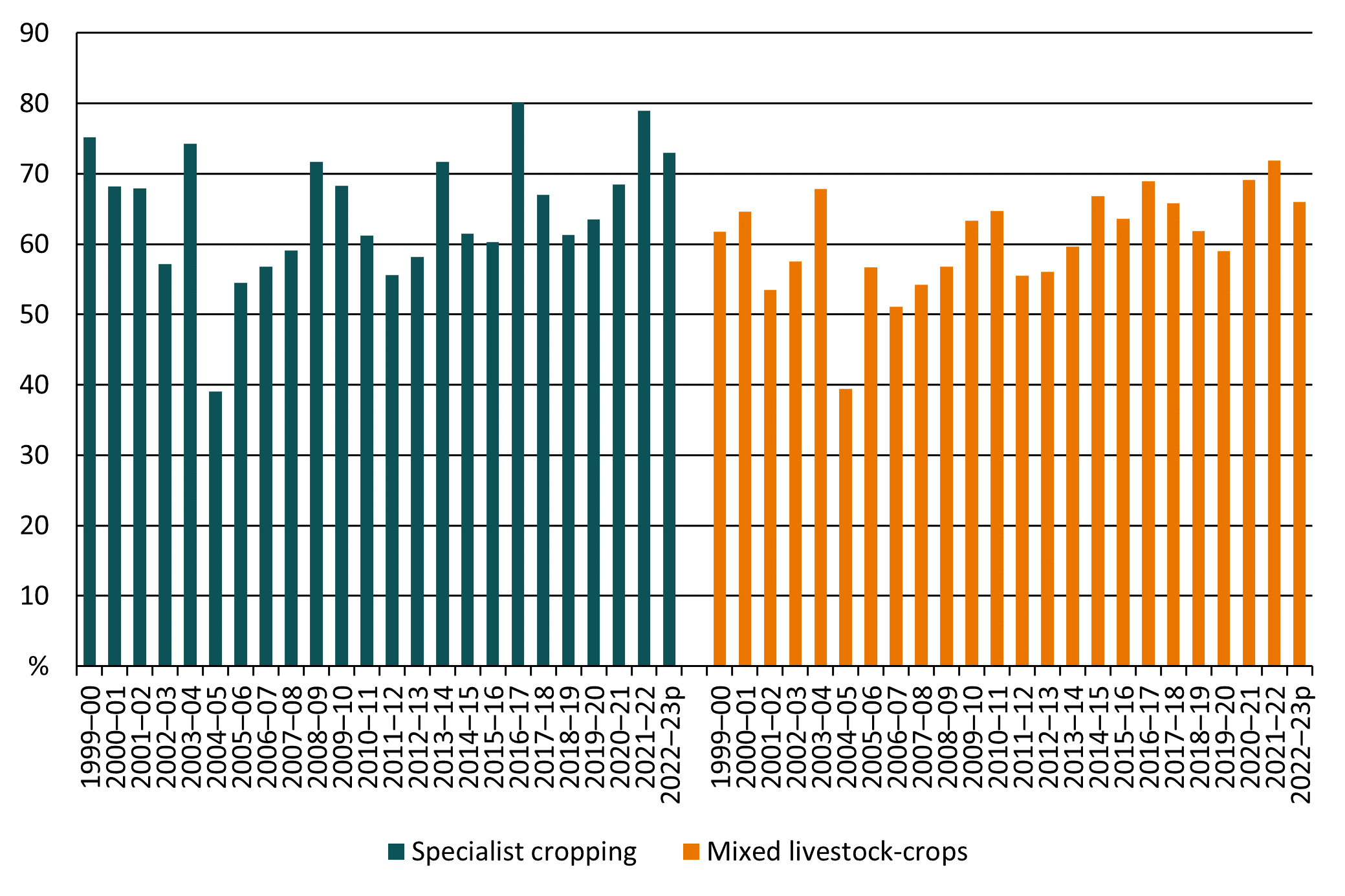

- The proportion of cropping farms investing in new capital each year averaged 67% for specialist cropping farms and 64% for mixed livestock-crops farms over the 10 years to 2021–22. In 2022–23—the most recent year for farm investment data—the proportion of cropping farms making capital additions declined, reflecting lower farm incomes in that year (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Percent of farms making capital additions, cropping farms, 1999–2000 to 2022–23

average per farm

Source: ABARES Australian Agricultural and Grazing Industries Survey

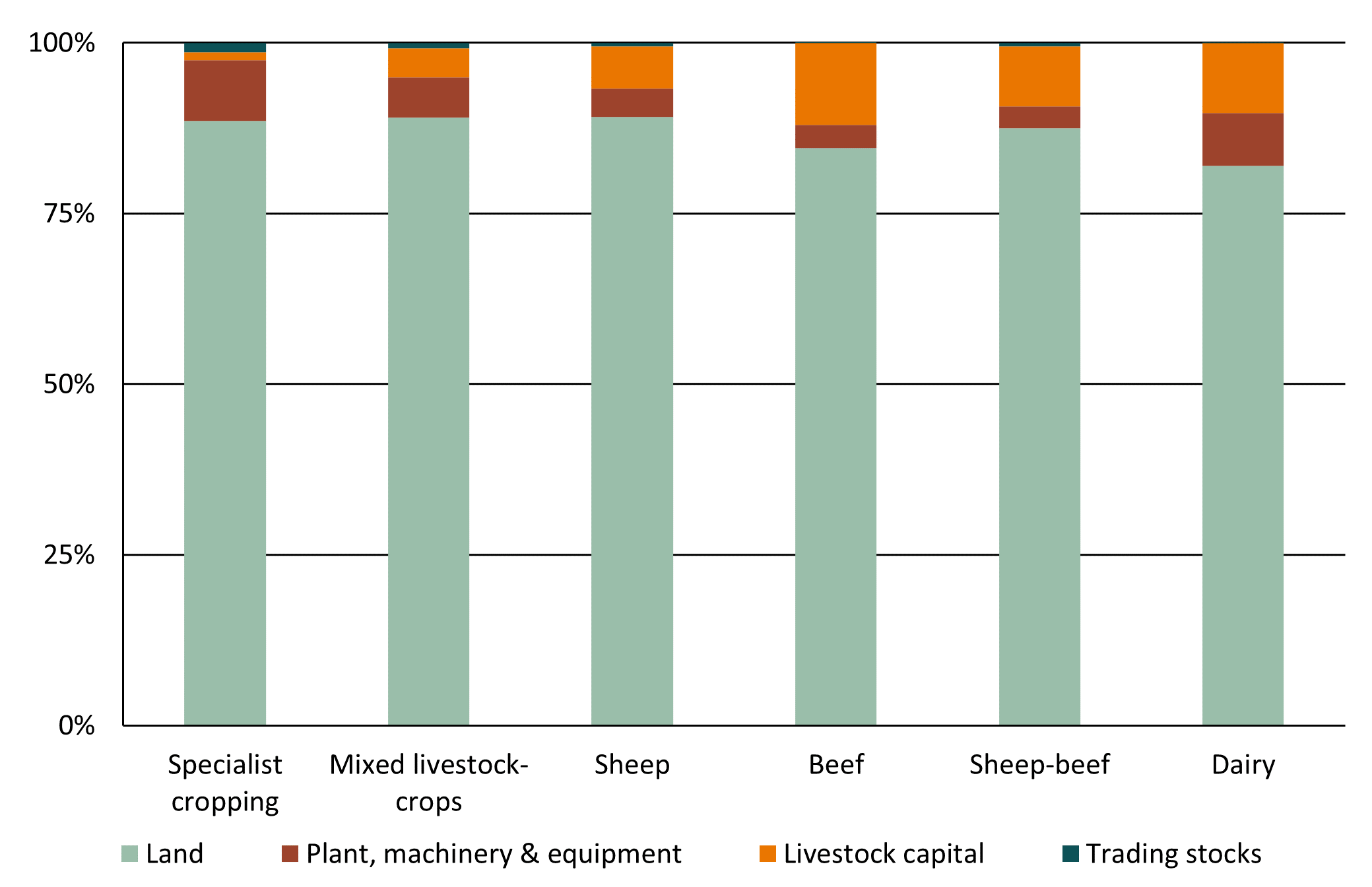

Types of farm capital

- The dominant type of capital used in Australian agriculture is ‘land’ capital. In 2022–23 land capital accounted for 89% of the total value of capital for specialist cropping farms and 89% for mixed livestock-crops farms (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Components of farm capital, broadacre and dairy farms, 2020–21 to 2022–23

average per farm

Notes: ‘Land’ capital is the market value of the land including the value of any fixed improvements such as buildings and structures, and permanently installed irrigation infrastructure. Trading stocks include the capital value of on-farm stocks of hay, fodder and grain. All values are expressed in 2023-24 dollars.

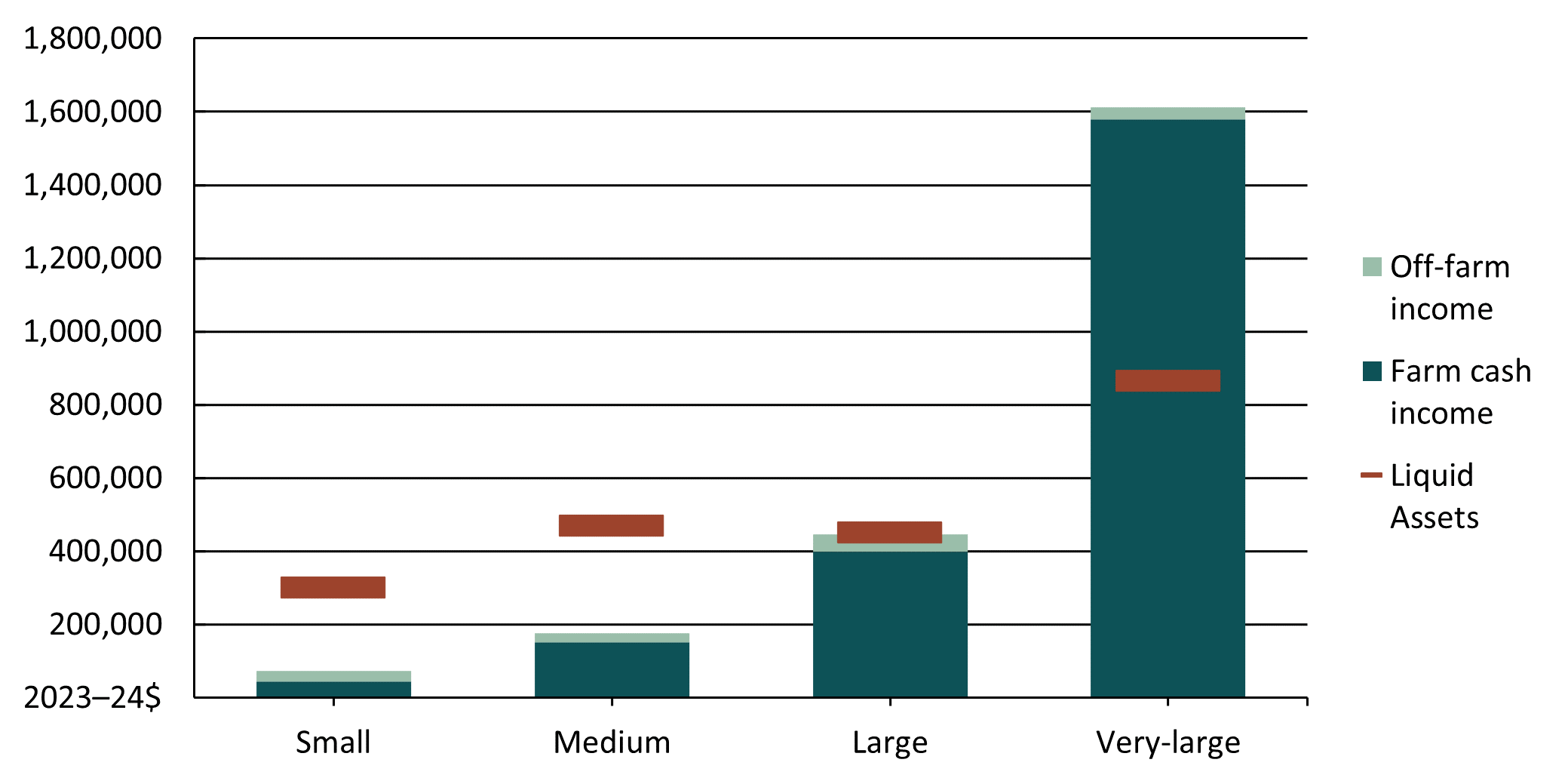

- Many cropping farms have substantial holdings of liquid assets relative to farm household income that makes them well placed to withstand short-term downturns in income, although there is wide distribution across farm sizes (Figure 6).

- Non-farm income increases business resilience to shocks to farm financial performance for many farms. In particular, small cropping farms sourced a large proportion of their household incomes (farm cash income plus non-farm income) from non-farm sources in from 2020–21 to 2022–23. The proportion of non-farm income was substantially lower for larger farms.

- Farm Management Deposits (FMDs) are an important financial risk management tool for many cropping farms and forms part of their liquid assets. At 30 June 2023, an estimated 41% of cropping farms held FMD accounts, at an average value of $446,600 per farm.

Figure 6 Farm household income and liquid assets by farm size, cropping farms, 2020–21 to 2022–23

average per farm

Source: ABARES Australian Agricultural and Grazing Industries Survey.

The data in this report is drawn from ABARES Australian Agricultural and Grazing Industries Survey (AAGIS). AAGIS covers broadacre farms with an estimated value of agricultural operations (EVAO) greater than $40,000. Broadacre farms account for around 62% of all Australian farm businesses and they include the following industries (defined by Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC)):

Cropping farms

Wheat and other crops farming: Specialised producers of cereal grains, coarse grains, pulses, and oilseeds.

Mixed livestock-crops farming: Farm businesses engaged in producing sheep and/or beef cattle in conjunction with substantial activity in broadacre crops such as wheat, coarse grains, pulses and oilseeds.

Sheep-Beef Cattle Farming: Producers who have a mix of sheep and beef cattle. Farms classified to sheep-beef industry combine sheep and beef enterprises such that neither enterprise dominates the other.

Livestock farms

Beef cattle farming: Specialised producers of beef cattle.

Sheep farming: Specialised producers of prime lambs, sheep or wool.

Sheep-beef cattle farming: Producers who have a mix of sheep and beef cattle. Farms classified to the sheep-beef industry combine sheep and beef enterprises such that neither enterprise dominates the other.

AAGIS provides a wide range of information on the current and historical economic performance of farm business units, including farm costs, receipts, income and profit, debt, assets, farm capital and labour, industry and farm size.

To reduce respondent burden and complexity of the survey ABARES developed a model-based approach to producing its projections of key estimates. Data in this report for 2023–24 are derived from this model.

Further information on ABARES farm surveys and survey methodology can be found on the ABARES website.

All dollar values in this report are expressed in real terms, adjusted to 2023–24 values. Adjusting to real terms removes the effect of inflation and allows financial values of different time periods to be compared in like terms. ABARES adjusts for inflation using the consumer price index produced by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024).

Previous versions of this and related reports.

Farm surveys definitions and methods

Further information about our survey definitions and methods.

The Farm Data Portal is an interactive tool containing all data from ABARES surveys of broadacre and dairy farms, and outputs from those surveys, all in the one location.