Screwworm fly: a continual threat

No. 109

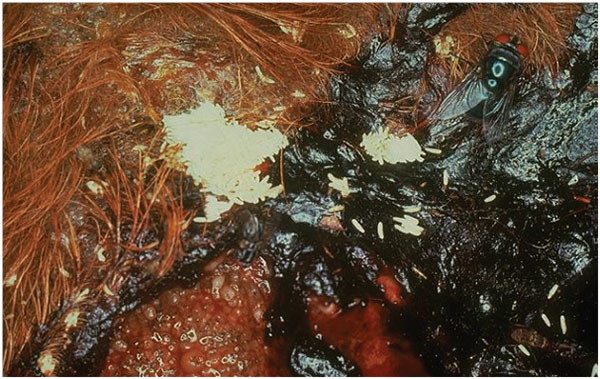

Chrysomya bezziana and Cochliomyia hominivorax (order Diptera, family Calliphoridae), the Old World and New World screwworm flies respectively, are two species of parasites capable of infesting any warm-blooded animal (including humans), causing myiasis in their vertebrate hosts (Figure 1). Screwworm fly populations are distributed across most tropical and subtropical regions. Their larvae, which are obligate parasites (only capable of existing in living tissues), are capable of causing significant tissue damage in hosts, leading to substantial costs to manage the pest and its effects in endemic countries.

Screwworm flies are exotic to Australia and are notifiable under state and territory legislation. All suspected cases should be reported to the relevant state or territory government animal health authority.

Figure 1 Screwworm fly myiasis affecting an animal. Photograph courtesy of CSIRO

Epidemiology

Geographic distribution

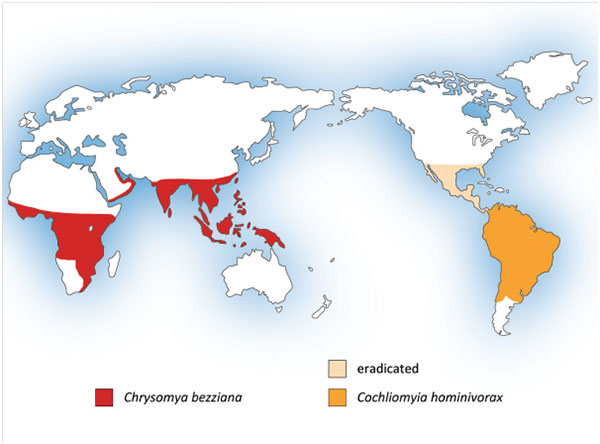

Both C. bezziana and Co. hominivorax have very similar biology and fill identical ecological niches in geographically separate regions, confined to Africa and Asia and the Americas respectively (Figure 2). The geographic range of both species is heavily dictated by climatic conditions. The population is maintained in tropical climates year-round and the geographic range expands and contracts with seasonal fluctuations in climate at the limits of its distribution.

Figure 2: Geographical distribution of C. bezziana (red) and Co. hominivorax (orange)1

Lifecycle

The lifecycle of both species is similar and can vary from 18 days to around 2 months depending on environmental temperatures. Adult flies lay their eggs in masses at the margins of wounds or mucous membranes, and they hatch into larvae 12–20 hours later. The larvae undergo three stages (instars) of development over four to eight days, during which they feed on the living tissue of the host. When mature, the larvae emerge and drop from the wound, burrowing into the ground to pupate. Pupae can emerge as adults in less than one week but are also capable of surviving for extended periods in cooler conditions. This ability can allow survival of pupae over-winter and re-emergence during more favourable temperatures, resulting in seasonal outbreaks.

Although the larvae are obligate parasites, screwworm flies are able to survive for up to several weeks in the absence of a suitable wound to infest. They may expand their population exponentially when favourable climatic conditions prevail and suitable hosts become available.

Clinical signs and diagnosis

Adult flies are attracted to wounds and other moist tissues, including mucous membranes and the umbilicus of neonates, where they lay their eggs. When hatched, the larvae feed on the tissues of the host, using mouth hooks to burrow into the tissue, causing significant tissue damage and rapid expansion of the original wound, causing more severe myiasis than other species of flies. The tissue damage produces a characteristic odour, attracting gravid flies that lay additional egg masses at the wound site.

The clinical signs and effects of screwworm fly myiasis can vary according to the site and severity of infestation. They may be occult infestations (for example, in the prepuce of males or oral cavity); clinical infestations causing irritation, secondary infection and growth rate reduction; or, severe infestations causing death. Positive identification of the screwworm larvae is used to diagnose and differentiate infestation from other forms of myiasis.

Host susceptibility

Screwworm flies can infest any warm-blooded living animal. Infestations are most common in mammals and rare in birds. The likelihood of strike is increased when animals have wounds of any kind (however minor); tissue disruption due to other disease processes or environmental influences; or altered behaviour reducing their ability to protect or care for the skin and body orifices.

Treatment options

Treatment of infested animals is similar to other causes of flystrike and includes cleaning and debridement of the wound, including physical removal of larvae; topical treatment of the wound to kill any remaining larvae; and systemic treatment with an insecticide as prophylaxis against re-infestation.

Insecticidal treatment may also be used prophylactically in higher risk animals (e.g. at the time of castration). Screwworm flies are highly susceptible to a broad range of insecticides, with relatively little resistance reported in endemic areas where they are widely used. However, widespread use of a limited range of insecticides could lead to development of resistance.

How could screwworm fly enter Australia?

Screwworm fly could enter Australia through either arrival of an infested live animal (including humans), or through arrival of live off-host life-cycle stages (i.e. adult flies or pupae). Although generally considered a low risk of introduction, both entry pathways have occurred in the past and could occur again.

Infested hosts

Australia implements biosecurity practices to minimise the risk of exotic diseases and pests, such as screwworm fly, entering Australia. However, both humans and animals could enter Australia via several illegal or unregulated pathways, including movements across the Torres Strait, landings of foreign fishing vessels or private yachts, wildlife smuggling, and natural migration of birds and bats.

In May 1992, a woman returned to Australia from Brazil with live Co. hominivorax larvae infesting a wound on her neck.2 In this case, the fact the woman sought early medical attention prevented the fly completing its lifecycle and becoming established. Although it has been 20 years since the last introduction via this pathway, the threat of future introductions remains. International passenger movements have more than doubled over this time.

Live flies or pupae

It is thought that live screwworm flies or pupae might be able to enter Australia via natural dispersal, flying across the Torres Strait, potentially assisted by prevailing winds, although this pathway of entry has not been confirmed. Live flies or pupae could also arrive via assisted spread, hitching a ride on vessels or aircraft entering Australia. Commercial aircraft and shipping movements have a known role in the introduction of insect pests to new geographical areas. Livestock vessels, in particular, are known to be highly attractive to adult screwworm flies, possibly even after livestock are unloaded, and are considered responsible for introducing Co. hominivorax into Libya in 1988 and the introduction of C. bezziana into several Gulf countries over the last 35 years3.

What would happen if screwworm fly were introduced?

Screwworm flies thrive in hot, humid conditions and prefer moderate levels of vegetative cover, which provides shade. They are susceptible to extremes of both temperature and moisture. Climatic modelling has shown that most of tropical northern Australia and the eastern seaboard offer a suitable climate for screwworm fly survival, with this area extending further south in hotter seasons or years4.

With large feral animal populations present in the north, large numbers of both extensively and intensively reared livestock along the eastern seaboard, and the human population in highest density along Australia’s coast, there is a genuine risk of screwworm fly becoming established if it managed to gain entry into Australia.

The potential economic impact of screwworm fly infestation on the livestock sector includes production losses, animal deaths, and increased labour and treatment costs. If screwworm flies were to become endemic in Australia, direct annual costs to the livestock sector have been estimated at approximately AUD $500 million, and the total economic impact, when indirect and public health costs are accounted for, is estimated at AUD $900 million5.

Given the significant economic and ecological impact an incursion of screwworm fly could have on the Australian livestock sector and wider community, the current policy is to eradicate screwworm fly as soon as possible. Eradication would be reliant on the cooperation and compliance of affected industries.

Current prevention and preparedness activities

The Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry implements a number of biosecurity practices to minimise the risk of introduction of exotic diseases and pests, including screwworm fly. For example, all live animals imported into Australia are required to undergo some form of health inspection and quarantine, and “disinsection” (treatment with an insecticide) is carried out on returning livestock vessels and commercial aircraft landing in Australia.

The Screwworm Fly Freedom Assurance Program (SWFFAP), managed by Animal Health Australia, is responsible for coordinating surveillance for the early detection of a screwworm fly incursion. This includes monthly trapping for adult screwworm flies in the Torres Strait and at several major ports around Australia; myiasis monitoring conducted during animal health surveillance activities in northern Australia; and reporting of myiasis cases in humans and animals to state or territory departments of health and agriculture.

Australia’s preparedness strategy for an incursion of screwworm fly,6 part of the Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN), outlines the national response plan to control and eradicate screwworm fly from Australia if it was introduced.

Implications for Australian veterinarians

Although the last known introduction of screwworm fly into Australia was 20 years ago, there remains a continuing threat of a future incursion through any of the potential pathways described previously. This threat may even be increasing, as international trade and passenger movements continue to increase.

Early recognition and warning will be the key to successful control and eradication should an incursion of screwworm fly occur in the future. Australian veterinarians should remain vigilant to the possibility of an incursion and all cases of myiasis in pets or livestock should be investigated to determine the species responsible. Any cases of possible screwworm fly myiasis should be reported to state or territory animal health authorities, or by calling the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline (see below).

If you suspect that you have seen a case of screwworm fly myiasis, please telephone the Emergency Animal Disease Hotline on 1800 675 888.Skye Fruean

Animal Health Policy

Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry

References

- Mahon R. The R & D required prior to implementation of an OWSWF SIT program in Australia. In: Report to Animal Health Australia. CSIRO Entomology, Collingwood, 2005.

- Searson J, Sanders L, Davis G, Tweddle N, Thornber P. Screw-worm fly myiasis in an overseas traveller, Commun Dis Intell 1992;16:239.

- Rajapaksa N, Spradbery JP. Occurrence of the Old World screw-worm fly Chrysomya bezziana on livestock vessels and commercial aircraft. Aust Vet J 1989;66:94-96.

- Sutherst RW, Spradbery JP, Maywald GF. The potential geographical distribution of the Old World screw-worm fly, Chrysomya bezziana. Med Vet Entomol 1989;3:273-280.

- Urech R, Green P, Muharsini S, et al. Improvements to screw-worm fly traps and selection of optimal detection systems, final reports 2008. Meat and Livestock Australia, Sydney, 2008.

- Animal Health Australia. Disease strategy: screw-worm fly (Version 3.0). In: Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN). 3rd edn. Primary Industries Ministerial Council, Canberra, 2007.