Emissions management means knowing the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced by a farming business and making informed decisions to:

- reduce GHG emissions through different production decisions or technologies and/or

- capture and store carbon from the atmosphere in carbon sinks, such as vegetation and soil.

Undertaking the agricultural practices and ways of managing land to achieve this is also known as ‘carbon farming’. This Knowledge Hub may link to external resources that have different terminology.

Why managing emissions is good business management

Productivity and sustainability are key objectives for farmers. Emissions management can align directly with these goals.

For example, emissions management can help:

- improve animal health and productivity, such as using genetic selection and feed efficiency to turn off livestock earlier or increasing access to vegetation that provides shade and shelter

- improve soil structure and fertility, through activities such as increased vegetation and minimal tillage harvesting

- improve nitrogen use efficiency through fertiliser management practices

- use water more efficiently, such as through precision agriculture

- meet growing market and supply chain expectations around lowering the emissions intensity of production

- identify new income opportunities through environmental markets such as carbon and nature repair markets

- support biodiversity by strengthening ecosystems, such as through restoring vegetation or wetlands and waterways.

Find out more about possible on-farm benefits.

GHG sources and sinks on farm

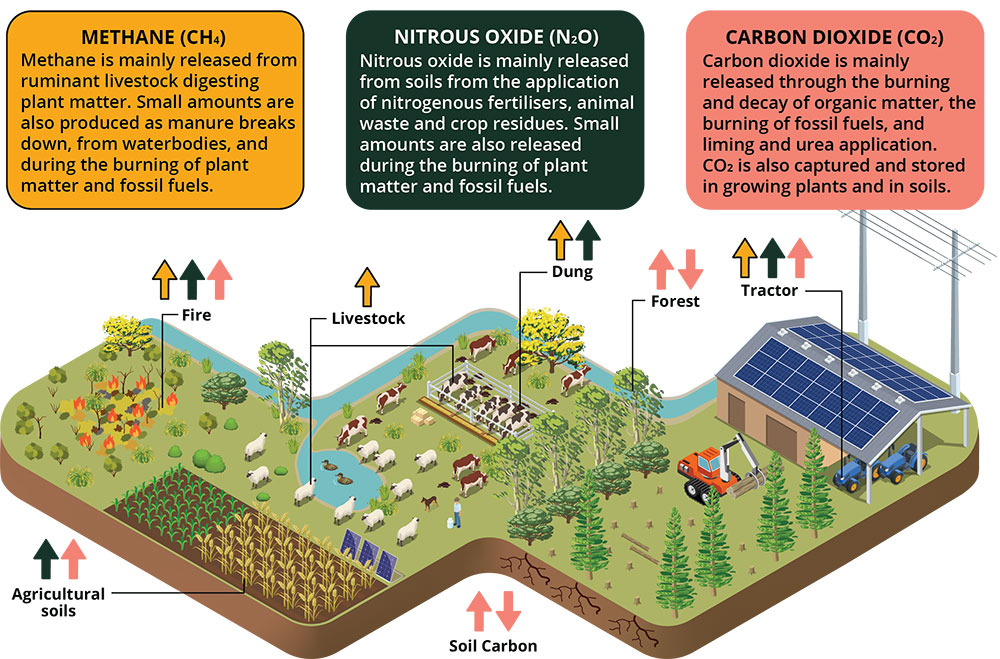

Agricultural activities emit several greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane. In 2023-24, those emissions made up 19.6% of Australia’s net emissions, including energy and fuel use.

Australia’s carbon sink is equivalent to -16.5% of Australia’s net emissions. Agriculture and land use are part of this sink.

GHG emissions released and stored on farms

GHG sources on farm

Every farm is different, but understanding the main sources of emissions can help identify where to focus emissions reduction activities. The main sources of emissions from agriculture are:

- enteric fermentation (mainly cattle and sheep), which is a natural digestive process of livestock that produces methane

- agricultural soils, which produce nitrous oxide from fertilisers, animal waste and crop residues

- manure management, which produces methane and, in some cases, nitrous oxide

- fuel and energy use.

Carbon sinks on farm

Farms can also capture and store carbon. Storing carbon removes carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere.

Plants and animals use, store and release carbon in different ways as part of the carbon cycle.

PROFESSOR RICHARD ECKARD: This is an explanation of the carbon cycle in agriculture.

It's based on a grazing system, but the same principles apply to a cropping system.

It all starts with sunlight energy and the process of photosynthesis in plants, which allows plants to capture carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and lock it away into a plant.

You will notice that we've highlighted the letter c in its various forms of carbon, showing that carbon in CO2 is a gas, but carbon in the plant is CHO, which is a sugar, not a gas. The key point is that carbon takes many forms as it cycles through our agricultural systems.

In a cropping system, we would then harvest that plant. In a grazing system, an animal will graze the pasture and convert the carbohydrate into animal products.

The majority of the carbon consumed by the animal is belched out or breathed out as CO2 back to the atmosphere.

The majority of the animal products or crop products, eaten by humans is also respired back to the atmosphere within 12 months as CO2.

If that was all that happened, the carbon cycle would be completely balanced, with all inputs returning to the atmosphere in the same form within a short period of time.

However, a small amount of carbon entering the rumen of the animal is converted into methane, CH4, which is carbon in another gaseous form. Methane is fundamentally different to CO2 and has a far higher warming potential in the atmosphere for the duration that it's there.

The animal defecates, and so there's faecal carbon in an organic form going back to the soil.

Plants will leave litter on the soil surface as a form of organic carbon.

As the plant grows, it produces roots, and these roots leave carbon behind either as root fragments or as root exudates of sugars.

This organic form of carbon in the soil can either be in a larger fraction, which we call the particulate organic carbon, and turns over fairly fast through microbial action, perhaps in hours through to a few years.

The smaller, more resistant fractions of organic carbon in the soil are called humus.

These are the more resistant fractions that last for decades through to hundreds of years.

In the soil, there are billions of microbes that then work actively on this organic carbon as their food source, actively breaking down the carbon to release the stored nutrients back to the soil to allow the crop or pasture to grow.

In the process, these microbes then release the carbon stored in the organic material as carbon dioxide back to the atmosphere, and the carbon cycle completes itself.

In a cropping system, this process of mineralization may release 30 to 50 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare per year out of the soil organic matter. In a dairy pasture system, it can be as much as 250 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare per year from the organic matter.

The point of carbon farming is to capture and make that cycle as efficient as possible so that we can transfer as much of the carbon from the atmosphere into product that we're interested in producing, which could be meat, wool, milk, grain, and crops.

Carbon farming is therefore focused on maximising the carbon from photosynthesis through to a product that goes to market as efficiently as possible.

In the process, good carbon farming would aim to leave as much carbon in the soil as possible, capture some of the carbon in trees growing in the landscape, and minimise the amount of carbon lost as methane and as a nitrogen gas.

The way that land is used and managed can help to store more carbon from the atmosphere. Carbon can be stored on farms in two main ways:

- In vegetation (such as trees and grasslands), carbon is stored in the stems, trunks and roots.

- In soil, carbon is stored in living and dead organic material.

The State of the Environment report (DCCEEW) explains the range of ways that carbon can be stored.

By understanding these sources and sinks, farmers can consider practical changes that make their farm more efficient and reduce emissions. Examples might include maximising herd productivity to reduce methane or using fertiliser as efficiently as possible to cut nitrous oxide emissions.

Learn more about greenhouse gas cycles in agriculture (Agriculture Victoria) and agricultural emissions (CEFC).

Scopes of GHG emissions

Along with different sources of emissions on farms, there are also different categories of emissions, or ‘scopes’. These scopes help separate emissions a business produces directly, and the emissions linked to its suppliers and partners.

- Scope 1: Direct emissions from sources that an organisation owns or control directly. On a farm that might include fertiliser use or emissions from livestock and manure.

- Scope 2: Indirect emissions generated from grid electricity. On a farm that might include electricity to heat and cool buildings.

- Scope 3: Indirect emissions that occur in the supply chain. On a farm that might include indirect emissions from producing and transporting animal feed or fertiliser.

See more information on what’s included in each scope for farm emissions (CEFC).

If you want to measure and manage emissions on your farm, you need to understand these scopes. They help you see the full picture of where emissions come from on your farm.

The different emissions scopes are also useful for understanding the role supply chains play in supporting emissions reduction on farm. Learn more about how supply chains are supporting emissions reduction efforts.

How to manage emissions

A range of existing and emerging technologies and practices are available to manage emissions.

Activities that avoid or lower the amount of GHG emissions from agricultural production can include:

- improving your energy efficiency, such as through upgrading machinery or installing renewable energy

- improving nitrogen use efficiency

- improving performance of livestock, such as through herd nutrition, feed efficiency and genetics.

Activities that store carbon can include:

- planting trees, such as for shelterbelts

- allowing vegetation to grow back (often by fencing off areas)

- changing soil management practices.

See soil carbon sequestration: a guide to climate-smart farming (AgriFutures).

The best emissions management approach for you will depend on your location, climate, type of land, type of farming operation, and your goals.

Learn more about ways to reduce your emissions on farm.

Environmental markets

If you would like to earn income from storing carbon or improving biodiversity, there are two main Australian Government schemes:

Read more about environmental markets.

Additional resources

Explore further resources on emissions management and storing carbon.

State and territory resources

State and territory governments have resources to help you understand emissions management:

- New South Wales: Low Emissions Agriculture

- Queensland: Queensland Low Emissions Agriculture Roadmap 2022–2032

- South Australia: Understanding your carbon footprint

- Tasmania: Climate Change and Agriculture

- Victoria: Carbon and Emissions Resource Kit

- Western Australia: Mitigating climate change by lowering emissions

See more

Learn about emissions management:

- AgriFutures: A farmer’s handbook to on-farm carbon management (free download).

- CEFC: Learn more about agricultural emissions.

- DAFF: How agriculture and land can contribute to Australia’s net zero goal.

- DCCEEW: Learn more about policies and programs to reduce agriculture emissions.